Worth a Thousand Words—

Graphic Biographies of Artists’ Lives

By Sean Bieri

As a lifelong fan of comics, my college years could not have come at a better time. In the late 1980s, the independent comic book scene was exploding. My housemate introduced me to his stash of Raw magazines, the cutting-edge “comix” anthology that first serialized Art Spiegelman’s Maus. From there I went on to discover Love & Rockets, Acme Novelty Library, and dozens more artistically mature comics, some hefty enough to merit the still new label “graphic novels,” that gestured toward a future for comics beyond their super-heroic, kid-stuff reputation.

That future eventually arrived and now even the blandest chain bookstore carries a wide selection of comics for all ages. However, that hard-won term “graphic novel” has become more confusing than ever since many of the best new comics are not fiction at all but biographies or memoirs. In particular, there has been a spate of graphic biographies in recent years that take fine artists as their subjects. (Ironic, perhaps, since us “comix” partisans always insisted that cartoonists were serious artists too!) There are almost too many to list—Jean-Michel Basquiat, Frida Kahlo, and Niki de Saint Phalle each have no fewer than two comics biographies devoted to them—but here is a round-up of some of my favorites.

From 2003, an early entry in the genre is Nicolas Debon’s Four Pictures by Emily Carr—a brief but compassionate overview of the life of the late-blooming Canadian painter whose luminous landscapes have drawn comparisons to Georgia O’Keeffe’s. The book comprises four chapters: Carr’s encounter in her 20s with the Native people of Vancouver; her frustrated attempt to study art in Paris; her rediscovery at age 56 with her first major exhibition and her introduction to the artists of the famed Group of Seven; and her later years working out of a trailer in the woods, where she made some of her greatest paintings. Debon is a French-born illustrator, and his simply drawn characters—Carr’s face is rendered with dots for eyes and a dash for a mouth—reflect his childhood love of Tintin and other European comics. His pastels drawings suggest Carr’s own work, and the moments he chooses to illustrate trace the painter’s life elegantly and succinctly.

Fabrizio Dori’s art in Gauguin: The Other World also beautifully evokes his subject’s work, and he quotes a number of Paul Gauguin’s paintings directly. Dori switches between flat, saturated color when depicting the painter’s time in Tahiti and woodcut-style graphics with a limited palette for Gauguin’s voyage into the afterlife. Gauguin dies early in the book and relates his life story in retrospect to his guide into the beyond—one other than the Spirit of the Dead, the otherworldly entity watching over the prone nude girl called Teura in the artist’s best-known work. Gauguin is given the floor for most of the book, allowed to relate his struggles and motivations from his own perspective. Readers looking for an unequivocal critique of the artist’s transgressions—his abandonment of his family in Denmark, his romanticization of the Polynesian “primitives,” and his marriage to the 13-year-old Teura—may be left frustrated. The Spirit of the Dead, like the other island deities, is bemused by Gauguin, who “like all white men… had a hole in his breast… where evil thoughts are born.” He grants the painter, in his final moments, “the possibility of leaving this life without regrets” by choosing to stay in Tahiti rather than return to France and his eventual ruin. But Gauguin, by his own admission selfish and merciless in his pursuit of freedom, has no regrets; what he sought was “on a painting’s surface, not in reality,” and having found it in his art, he dies, by Dori’s telling, in relative peace.

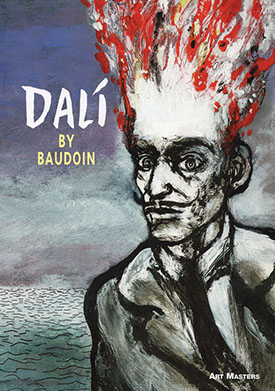

Edmond Baudoin’s art has little in common stylistically with that of Salvador Dalí. As unreal as Dalí’s scenes are, they are rendered with precision and polish, where Baudoin’s ink drawings are loose, brushy, and expressive. He does mimic Dalí’s collaging of multiple images and symbols, either to draw connections between events and ideas, or to reveal the inner thoughts of characters. Baudoin introduces two guides, a young man and woman, who discuss Dalí’s evolution from literal enfant terrible to art world titan and eccentric celebrity, as they stroll through pages that swirl with images from the painter’s life. There’s a searching, probing quality to the narrative: our guides are often interrupted, supplemented, questioned, or corrected by passers-by, a Greek chorus of ants straight out of Un Chien Andalou, the cartoonist, or by Dalí himself. While the book is predominantly black-and-white, vivid splashes of color are employed for Baudoin’s depictions of Gala, Dali’s indispensable wife and muse, to convey her effect on the painter’s psyche. In one six-panel sequence, depicting Dalí’s first meeting with Picasso, Baudoin succinctly illustrates the pioneering modernist’s influence on the younger artist: for three panels, Picasso silently jabs his finger at some of his own paintings, before showing Dalí to the door. “Got it?” he asks Dalí at last. “Got it,” Dalí replies. When the Surrealist’s art shifts late in life to a “return to classicism,” Baudoin’s approach changes too. In a wonderfully meta move, he yanks his female narrator out of the fantastical scenes from earlier in the book and into his more mundane studio, to her chagrin. She critiques the art on his drawing board: “Your interpretations (of Dali’s paintings) are very eccentric. Betrayals.” “That’s because I’m crazy,” Baudoin tells her, “just like him.”

(Left) Edmond Baudoin, Dalí, 2016. 159pp. (Right) Image from the text. Photos: SelfMade Hero.

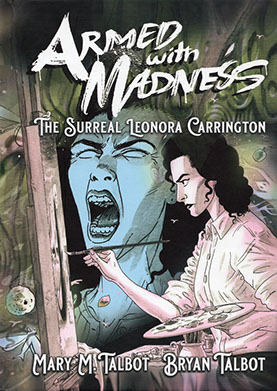

Cartoonist Bryan Talbot’s career stretches back to the 1960s underground scene. His Adventures of Luther Arkwright, a trippy tale of a dimension-hopping psychic warrior, is one of the earliest British graphic novels. The strange story, then, of a psychologically troubled British Surrealist who kicked against the constraints of polite society and occasionally transformed into a wild animal is right up Talbot’s alley (“I’m mostly a horse,” Leonora Carrington announces on page one by way of introduction, “but sometimes a hyena.”). Written by Bryan’s wife and frequent collaborator Mary M. Talbot, Armed With Madness: The Surreal Leonora Carrington follows its subject from a creative but troubled childhood (her mother nurtures her artistic pursuits, while her domineering father slowly morphs into a fuming steampunk robot), to a life-changing encounter in college with the work of Max Ernst (standing before one of his collages, Carrington’s chest bursts into flames), then to a more intimate encounter with Ernst himself (he becomes a bird to her horse as they make love in midair). Leonora is soon running with an all-star cast of 1930s modernists, but internecine political squabbles, Ernst’s jealous wife, the specter of impending war, and Carrington’s deteriorating mental health all conspire to disrupt the artistic idyll. As Carrington’s grip on reality falters, Talbot’s pages become claustrophobic collages of frog-faced caregivers, buzzing insects, syringes, and swastikas, bathed in blood red and acid green washes. Talbot’s art stabilizes when Carrington does, after she slips away from a sanatorium and makes her way to New York to escape the war. Carrington lived to be 94; the book closes with the elderly artist dispensing advice to a small group of earnest students: “People over seven and under seventy are very unreliable,” she tells them, “especially if they’re not cats.”

(Left) Mary M. Talbot and Bryan Talbot , Armed with Madness: The Surreal Leonora Carrington, 2023. 143 pp.

(Right) image from the text. Photos: SelfMade Hero.

Thomas Girtin may be the most obscure artist yet to receive the graphic bio treatment, but his is over twice as long as most of the books discussed here. That is because much of Thomas Girtin: The Forgotten Painter, by Argentinian cartoonist Oscar Zarate, is devoted to the stories of three old friends in modern day London, amateur artists who meet for drinks every month after a figure drawing session. Sarah is a devout Catholic and still lives in the shadow of a more ambitious art school friend. Arturo is a cynical refugee from the Argentinian coup of the 1960s who suffers from survivor’s guilt. Fred has been fired from his job for poking his nose into workplace corruption and is being followed by thugs intent on reburying the dirt he has dug up. It is Fred who first becomes obsessed with the life story of Girtin, a little-known 18th-century British landscape watercolorist whose only rival at the time was his friend J.M.W. Turner. Soon, Fred’s friends become intrigued by Girtin too. Each latches on to a different aspect of the painter’s story: Sarah responds to his emotional, even spiritual, approach to depicting nature; Arturo ponders his revolutionary politics and associations with the aristocracy; and Fred literally follows in the artist’s footsteps, making a pilgrimage to the chilly mountains of Wales to commune with Girtin’s spirit. Standing on a cliff where Girtin once stood, Fred asks the storm clouds growing overhead, “Why is it that when I look at your art, I feel I have all the answers?” Zarate illustrates the book with subdued watercolor over deft pencils, switching to sepia tones for flashbacks to Girtin’s life. The painter was just 27 when he died. Near the end of the book, the still-young ghost of Girtin speaks with the elderly shade of his old friend Turner, who admits that without Girtin, “I doubt I would have turned out the way I did.”

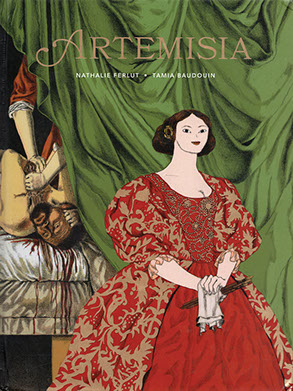

Artemisia Gentileschi, the 17th-century Italian painter whose fame has justifiably been on the rise in recent years, has two graphic biographies to her name. Nathalie Ferlut and Tamia Baudouin’s Artemisia is the slimmer of the two, illustrated in loose pencil drawings enhanced by digital coloring in a warm Baroque palette. The fictionalized narrative follows Artemisia from her youth as a student of her painter father Orazio; through the trial of family friend Agostino Tassi, who raped Artemisia when she was 18, an event that has become the most salient episode of her biography; to her later years as the first female member of the art academy of Florence and a renowned artist of rare independence.

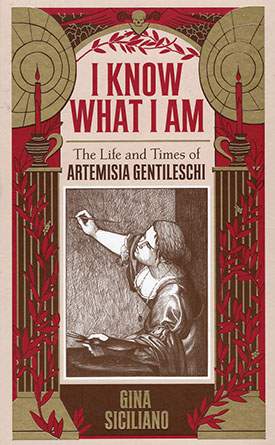

(Left) Nathalie Ferlut and Tamia Baudouin, Artemisia, 2021. 98pp. Photo: Beehive Books. (RIght) Gina Siciliano, I Know What I Am: The Life and Times of Artemisia Gentileschi, 2019. 279pp. Photo: Fantagraphics Books.

But while Artemisia is an engaging overview of its subject’s life,

Gina Siciliano’s I Know What I Am: The Life and Times of Artemisia Gentileschi is the more complex and intense of the biographies. Twice as long as Ferlut and Baudouin’s book even without its copious footnotes, I Know What I Am is exhaustively researched as well as highly personal (the author speaks in a preface of being a sexual assault survivor herself). On page one, a serious Artemisia stares out at the reader above a caption reading, “A girl artist in 21st-century Seattle writes about a girl artist in 17th-century Rome…” Using sketchy pen drawings softened somewhat by being printed in blue-gray ink, Siciliano first sets the scene. She portrays the brutal political and social situation in Rome circa 1600 and describes the rise of the most influential painter of the age, Caravaggio, before introducing Orazio and,finally, his talented daughter. Even before being assaulted by Tassi, the young Artemisia was groped by another associate of her father’s, Cosimo Quorli; Siciliano describes the painter’s first masterpiece, Susanna and the Elders of 1610 (arguably the greatest depiction of the popular biblical scene ever put to canvas) as depicting Cosimo and Tassi in the roles of the titular harassers. Siciliano depicts Tassi’s rape trial in sometimes excruciating detail; she renders much of it as a series of back-and-forth headshots of the various players—the judge, advocates, witnesses, the accused, and Artemisia. This technique might not normally make for great comics, but here it produces a staccato rhythm that amplifies the tension of the proceedings. The rest of the book follows Artemisia’s artistic and professional development, as well as her personal life and relationships (not least a friendship with Galileo), with similar sympathy and rigor. Summing up, Siciliano says, “Questions that scholars grappled with for years take on new life in the comics format.”

I have found that there’s a special intimacy to comics as an art form that delivers a reading experience ideal for biography and memoir. But their hybrid nature—part visual, part textual—may be what makes them especially suited to telling the stories of visual artists. Will Eisner, the pioneering cartoonist who popularized the term “graphic novel” in the ’70s, called his own autobiography “Life, In Pictures.” It is as good an encapsulation of the appeal of comics biographies—of Rembrandt or Banksy, daVinci or Kusama—as I can imagine. (I am even in the early stages of creating a graphic artist’s bio myself…

stay tuned!).

“Sean Bieri, a cartoonist and graphic designer, has written on art for the Detroit Metro Times, Wayne State University, and the Erb Family Foundation among other outlets. He received both his BFA and a BA in Art History—28 years apart—From Wayne State. He is a founding member of Hatch, an arts collective based in the Detroit enclave of Hamtramck, where he lives. He is currently assisting Hatch in the renovation of the “Hamtramck Disneyland” folk art site.”

Nicolas Debon, Four Pictures by Emily Carr, 2003, book cover. Photo: Amazon.com.

Fabrizio Dori , Gauguin: The Other World, 2016. 141 pp. Photo: SelfMade Hero.

Oscar Zarate , Thomas Girtin: The Forgotten Painter, 2023. 392pp. Photo: SelfMade Hero.

Gina Siciliano, I Know What I Am: The Life and Times of Artemisia Gentileschi, 2019. Image from text. Photo: Fantagraphics Books.