Where I Find Ourselves

A reaction to: “Tom of Finland: Highway Patrol, Greasy Rider, and Other Selected Works,”at David Kordansky Gallery (January 13–February 25, 2023); Felix Gonzalez-Torres, at David Zwirner (January 12–February 25, 2023); Dean Sameshima: Being Alone, at Queer Thoughts (February 1–March 18, 2023).

by Paul Moreno

At the end of winter in New York City this year, three exhibitions by three queer men, working in different times and places, all took place at once. In viewing all these shows within days of each other, I found myself asking how these works all connected, and taken together, what picture they make. They formed a monochromatic landscape: the black and white drawings of Tom of Finland; the black candy, the monotone photos, and water on gray concrete of Felix Gonzalez-Torres, and the high contrast black and white photographs of Dean Sameshima. I also asked some friends (and myself) how they felt these works related to their own lives as gay men.

One of these friends, in the spirit of Lent, had given up posting nude selfies on the internet. He dealt with his urges to lay himself bare on the web by taking the pictures, (it is not the taking of the pictures that is the issue) and sending them to me privately, forsaking the excitement, the danger, and the subsequent likes and lurid comments from the many approbating eyes that come upon the pictures my friend posts on-line. At the same time that I was the recipient of his exhibitionism, I was presented with the challenge of explaining, to readers and my editors, how the drawings of Tom of Finland are not simply pornography. I do think they are pornographic in the sense that they are depictions of sex and sometimes quite explicit, but because they are so much more, I do not think they are pornography. I asked my aforementioned friend, what he thought of Tom of Finland. He admitted that he didn’t know much about the context in which the drawings were made but that they were sexy and, in a way, cute, that they were nostalgic and felt commercial (I'm paraphrasing).

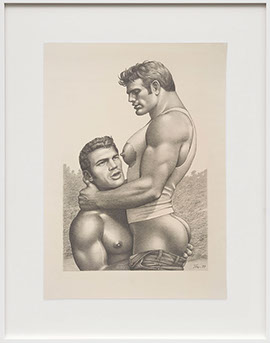

This was already enough to explain how the Tom of Finland images are not so purely prurient. His drawings, specifically the ones in the recent exhibition at David Kordansky Gallery in New York, were part of illustrative narratives about man-on-man intimacy and were intended to be viewed as such within the context of publications. Presenting these images in a gallery context makes the steamiest of the drawings less steamy, as they are viewed alongside the sweeter ones. For example, the first drawing in the show, Untitled (from "Setting Sail"), 1974, depicts two figures: the first, a light-haired and shirtless man aggressively smiles as he rests languorously in a double ender, his legs overboard, his billowing flared pants lilting in the breeze. The other figure is almost identical to the first, but with darker hair. He is nude—very nude—and appears to be pushing the dinghy with all his might. The image is sexy—one could imagine it being used to advertise a party at a gay bar. But the humor of this scenario takes the image to a place of cuteness in the sense that there is no threat of harm from these muscle men.No embarrassment or shame clouds their endeavor; no one in this image has tasted forbidden fruit, for the fruit was never forbidden here. But cuteness can also prick the darkest parts of us, inspiring a sense of abjection or violence for the guileless joy we are witnessing. Tom of Finland provokes a discomfort in a viewer who does not enjoy a man using his muscles in the romantic service of another man and if that man uses those muscles openly and with a smile, the discomfort can become a rage. These images are powerful not because of the oversized penises but because of the blatant smiles. I do not think a smile can be pornography.

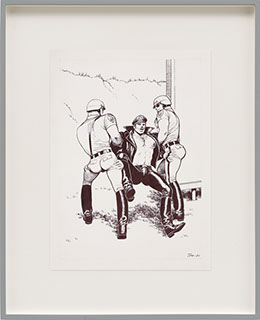

The drawings of Tom of Finland not only address the fear one may have of queers but also addresses the fear a queer may have of the non-queer, in particular the man in uniform. The cop, the soldier, the sailor, etc., symbolize the most extreme version of an existence in the world that gets called manly: the guy who gets jobs done and does not make a fuss and does not think too deeply about it. These men are banal. But the drag of their uniforms announces them fabulously. Many queers have harbored a fear of a man in uniform, but fear can be an aphrodisiac, and Tom of Finland shows us that. His fetishization for masculine drag that plays out through the characters in his drawings emerges from collages he made. These tidy and organized groupings of found and personal photographs, sometimes amended in pencil or ink, are group images of police, soldiers, bikers, cowboys, all glued down to pages of drawing paper. One such collage from the exhibition, Untitled, c. 1966–1990, is a gathering of men mostly cut from newspapers. He augments the images, adding boots, enhancing the thighs to jodhpur proportions, eliminating distracting background details. We see his mind at work, taking quotidian images and creating a personal mise en scène—literally moving the banal to a world of fetishization.

The drawings of Tom of Finland not only address the fear one may have of queers but also addresses the fear a queer may have of the non-queer, in particular the man in uniform. The cop, the soldier, the sailor, etc., symbolize the most extreme version of an existence in the world that gets called manly: the guy who gets jobs done and does not make a fuss and does not think too deeply about it. These men are banal. But the drag of their uniforms announces them fabulously. Many queers have harbored a fear of a man in uniform, but fear can be an aphrodisiac, and Tom of Finland shows us that. His fetishization for masculine drag that plays out through the characters in his drawings emerges from collages he made. These tidy and organized groupings of found and personal photographs, sometimes amended in pencil or ink, are group images of police, soldiers, bikers, cowboys, all glued down to pages of drawing paper. One such collage from the exhibition, Untitled, c. 1966–1990, is a gathering of men mostly cut from newspapers. He augments the images, adding boots, enhancing the thighs to jodhpur proportions, eliminating distracting background details. We see his mind at work, taking quotidian images and creating a personal mise en scène—literally moving the banal to a world of fetishization.

One day, my aforementioned friend sent me a handful of images of himself. We were a week and change into Lent at this point. He had sent me any number of pictures in the past, but somehow these were suddenly subtly different. They were less “look at me” and more “look at this.” They were more aware of composition or light or detail. They depicted fantasies being enacted. These images spurred in me a further realization of how Tom of Finland drawings transcend their sexual content. His drawings are not so much about wide open exploits of sexual abandon. Rather, they are the most private, intimate, vulnerable fantasies of an artist whose own experiences were restricted by the mores, laws, and plagues of his lifetime. He reacts to compulsory secret-keeping by making public gesture of aggressive pleasure. When we look at Tom of Finland’s collages and the subsequent sketches and final drawings, the images only feel salacious when their consumption is clandestine. When they are on the wall of a major U.S. gallery, when they are in the collection of MoMA and LACMA, they don’t lose their erotic power, but they open up and demand to be seen as the materials of an artist working in solitude to bring the world of his private life to the world of honest, open, public expression.

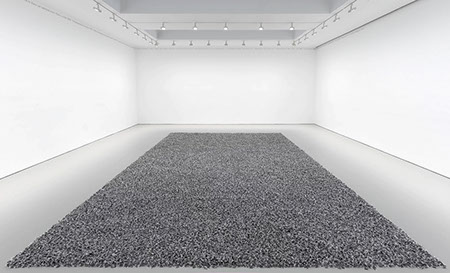

The liminal space where public rubs up against private is an exciting place for art to occur. Felix Gonzalez-Torres was an artist who deftly exposed the potential of this space. The most immediate way we witness this is in observing the ephemeral nature of his work, and the frequent resistance to there being an original object. For example, in the show at David Zwirner there was an example of his candy spill pieces, “Untitled” (Public Opinion), 1991. In one gallery a large rectangular carpet of the black licorice filled the center of the room. In a sitting area outside the gallery, a small mound of the candies was nestled into a corner. The sculpture was in two places at once but remains a single work. Viewers are invited to take from the piles of black candy, some were sucking away on their candies, and some slid the candies into their pockets. Some delicately took one; some would take a handful, disrupting the clean edge of the rectangle. Once the gallery was closed, the rectangle was corrected, and more candy might be added. Ideally the piece consists of 700 pounds of the black missile-shaped treats. This installation, which belongs to the collection of the Guggenheim, resists ownership, relying on its owner to execute it regularly according to its instructions, and allow, if not encourage, it be continuously dismantled by its audience.

The title “Untitled” (Public Opinion) already evokes something about one’s relationship to the community. Its “endless supply” of components are evocative of the many voices one hears in social media, the news cycle, word on the street, etc. Just like in our participation in those realities where we hear what we need or want to hear, here we pick the ones, the candy we want to consume. A slightly different read evokes something more ominous that was in the air during the artist’s life and is looming once again: the government being a pill that is poisoning the queer community through legislation and the judicial system. We are asked to swallow this, or we can ignore it, despite its undeniable determining force in our private lives.

The installation of “Untitled” (Sagitario), 1994–1995 is a work that the artist planned in the 90s but was being presented for the first time in the US at this exhibition. Two shallow circular pools of water are embedded in the floor; they are almost, but not quite, touching. The title, Sagitario, references a centaur, a creature that is half this and half that—two halves reliant on each other to make a whole. The double circle is a leitmotif throughout Gonzalez-Torres’s work. In two iterations of a sculpture called “Untitled” (Perfect Lovers), 1987–1990, and 1990, two clocks are placed side by side on the wall and started at the same moment and allowed to run until their times are no longer identical and perhaps even stop. In “Untitled” (March 5th) #1, 1991, two 12-inch mirrors are embedded into the wall at head height, forming an ever-changing split portrait. In “Untitled” (Double Portrait) a stack of posters printed with two gold rings, just touching, printed on a white field, is depleted, and replenished as viewers are asked to take a poster from the stack.

%201990%20rgb.png?crc=192053905)

Felix Gonzalez-Torres (Left), “Untitled" (Perfect Lovers), 1991. Two identical clocks hanging on the wall, set in synchronized manner at the same start time, operating with identical batteries. The clocks touch while showing the time which is running out. Inevitably, at some point they will stop; one of them will stop ahead of the other. MoMA. Photo: tripimprover.com.

(Right) “Untitled” (Death by Gun), 1990. Print on paper, endless copies. Stack: 9 inches ideal height x 44 15/16 x 32 15/16. Photo: moma.org.

“Untitled” (Sagitario) also operates as mirror, we see the reflection of others walking around it. As the water is “imperceptibly” exchanged between one pool and the other, we understand the metaphor about relationships between lovers, but it occurred to me for the first time when seeing this show, that Felix Gonzalez-Torres has established a relationship with me. But not only me. I have been making pilgrimages to see his work since I first encountered it in the 1995 Public Information exhibition at San Francisco Museum of Modern Art where I picked up a poster from “Untitled” (Death by Gun), 1990. I have a collection of Felix Gonzalez-Torres posters rolled up in a tube somewhere. I have a small basket filled with candies from various candy spills. I have lingered in galleries waiting for the go-go dancer to show up to activate “Untitled” (Go-Go Dancing Platform), 1991. I visited “Untitled” (Sagitario), with a friend, another fan of the work of FGT, as we affectionally call him. He activated the work by splashing water from one pool to another. I thought that was a bit silly and almost sacrilegious, but what I realized is that he, like me, desires our relationship with Felix Gonzalez-Torres. Those of us who really love his work have a relationship with him that is profound. It is almost as though his work is made for us, and we are part of it, it is almost eucharistic, if that is not too overstated. But if God is a circle, as they say, it is the circle drawn by Felix in which we see ourselves.

“Untitled”, 1994–1995, a second piece in this exhibition that was unrealized while the artist was alive, was also being presented for the first time. Filling a large dimly lit gallery, two freestanding billboard structures were situated side by side but facing in opposite directions, so that one could see the front of one and the back of the other. Janus-like, these are two faces looking in opposite directions, keeping sentinel, or just observing the crowd of on-lookers. The act of bringing a billboard inside echoes the way in which one internalizes public opinion. Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s work is periodically exhibited outdoors on actual roadside billboards and this act of bringing them inside also felt like the artist was pulling you aside to tell you something directly. Each billboard depicts one of Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s iconic images of a bird in flight against a cloudy sky. This wistful vision stirs feelings of lovers lost. Periodically, the viewing of these billboards was interrupted by a disconcerting racket—staticky, reverberating, hard to define. This noise was in fact a recording of the audience’s applause at a Carnegie Hall concert given by Kathleen Battle and Jessye Norman. This crowd sound shocks us out of their viewing relationship with this image of the sky. Once it ends, we reconnect to the image, or quietly exit alone.

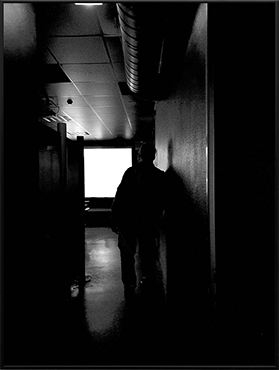

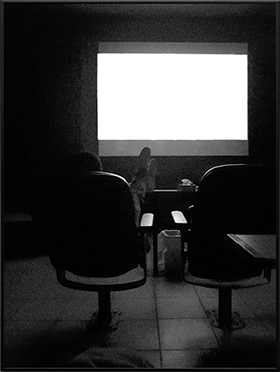

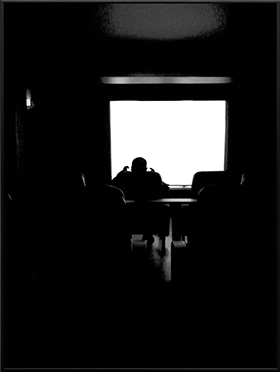

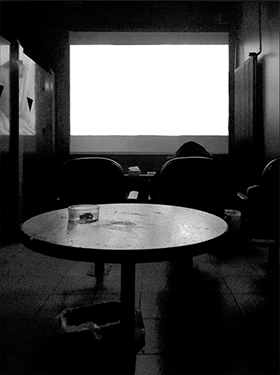

The images of the birds in flight formed a connection for me to the images in Dean Sameshima's “Being Alone.” In this show Sameshima shares a selection of fourteen pictures from a twenty-five-image series, Being Alone. Sameshima started these in 2015 and shot them until the onset of the Covid-19 Pandemic. They are strikingly high contrast. Each is a cave of deep blacks, and each has a bright white rectangle where the illuminated screen would be in an otherwise small, dark, porn theater. Shot from the rear of the theaters, the screen backlights the seats, the occasional box of tissues, the trash cans here and there, maybe a soda can or an ashtray, and, in each one, a solitary viewer that we see in silhouette as he gazes at the screen. The lone figures are like the silhouetted birds against Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s sky.

Dean Sameshima (Left), Being Alone (No. 13), 2022. (Right) Being Alone (No. 14), 2022. Archival inkjet prints, 23.4 x 16.5 inches. Photos: Queer Thoughts Gallery.

The solitude of the men in these photos resonates with the work of Tom of Finland and Felix Gonzalez-Torres. In Being Alone (No. 13), 2022, a man is slouched deep into his seat, we see the white of the sneakers he wears, elevated, ankles crossed, resting on some structure in front of him. He is relaxed, restfully watching the show. He has escaped the public sphere and retreated here where he is maybe not even in the depths of an erotic throe, but just alone, in his thoughts or perhaps with no thoughts at all. Being Alone (No. 14), 2022, is shot from a shallow passage, at the end of which we see a figure leaning against the wall, he has not quite entered the space but is viewing it. He is at the edge of this space that simultaneously possesses the premise of anonymity and/or connection and/or continued solitude, or to put it another way, a venue where the potential of his private self may be realized in public.

Dean Sameshima and I were born the same year, about 500 miles apart in the western US. His work evokes many of the same fascinations I had as a teen and younger man. The coded queerness of icons such as British musician Morrissey or the French theorist Roland Barthes. Sameshima fetishizes vintage porn and public sex as objects and ideas beyond their intended goal of immediate gratification. He and I came of age at a moment when the party of 1970s queer liberation had ended, and suddenly sex could kill you. I felt as though the wild life that I had been waiting to live was canceled and was replaced with waiting two weeks for the results of your anonymous testing. Sameshima’s work speaks to this. There is the fantasy of public sex being the outlet for private desire. There is the desolation that one might find once one has arrived at the public sex space. There is the realization that the public lives of the queers who came before us were not all hunky-dory. Not every gay man was at the orgies but there is always the hope that one will meet the perfect lover. Even if only fleetingly. Or maybe you don’t. There is no shame in being alone.

The picture, Being Alone (No. 9), 2022, is one of the strangest pictures in the bunch. The seated figure we see from behind is basically dead center. On either side of his head a sort of “air-quotes” shape rises over the chair. One assumes they are hands, but whose hands are they and what are they doing, what are they about to touch, or what are they carefully not touching? Is this figure being alone? There is the photographer. There is we the viewer. We are watching this private moment play out in public. At this exhibition we are actually in the midst of a crowd of fourteen figures, all facing the other way, all publicly lounging in their private lives. How we interpret this action, whatever scenario we provide ourselves, that is what we individually project into the white box before the guy in each picture. It may only be a bird in flight against a cloudy sky.

Dean Sameshima (Left), Being Alone (No. 9), 2022. (Right) Being Alone (No. 8), 2022. Archival inkjet prints, 23.4 x 16.5 inches. Photos: Queer Thoughts Gallery.

Or perhaps that screen is filled with an image from Tom of Finland’s Kake vol. 22—“Highway Patrol,” 1980. In this series of twenty-one drawings, two highway patrol officers, concealed in some shrubbery, spy a leatherman passing by on his motorcycle. Kake, the name of Tom of Finland’s frequent protagonist, is written across a roadside billboard. The officers take the biker behind the billboard where they have their way with him—the biker is more than willing to oblige. Once they are all satisfied that the law has been laid, we have a final drawing in which the spent biker smiles and waves at the departing cops. A truck passes by with the name “Tom” in large letters on its trailer. I can imagine the disconcerting racket it makes as our trio make their farewells.

It is clearly not only gay men who struggle with an aporia between their private lives and public selves, between the inner workings of their psyche and the persons they portray at the office. Queers however have had to force that divide especially profoundly. It is one thing if a straight white male discusses his peccadilloes at the office water cooler, because he is afforded the dignity of choosing privacy. A queer man during Tom of Finland’s era did not dare disclose his encounters for fear of censure, brutality, or even death. In a video on the website for the Tom of Finland Foundation, Touko Valio Laaksonen, Tom of Finland’s actual name, explains that he had always said he only intended his drawing for the audience that enjoyed them, but that he realized that was not true, that he wanted “so-called straight people” to see them, to understand that gay men had the right to enjoy sex and enjoy each other. Here he makes a strange distinction between a private public (his fans) and a public public (those who would be offended by his work). This private public is not dissimilar to the porn theaters in Dean Sameshima’s photographs. This public public is not dissimilar to a roadside billboard of a bird in flight against a cloudy sky, a billboard that anyone can see but only those who know the code will understand. In the time span from Tom of Finland’s first drawing to Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s dying of AIDS at age 38, with work unrealized, to Dean Sameshima’s theater-goers, queer people are still grappling with the public/private dichotomy. We attempt to conjure anonymity—simply being left to one’s devices, while at the same time evoking visibility, the resistance to having to operate behind closed doors. We do this by making art that leaves little to the imagination but that also leaves everything to the imagination.

Paul Moreno is an artist, designer and writer working in Brooklyn, New York. He is a founder and organizer of the New York Queer Zine Fair. His work can be found on Instagram @bathedinafterthought. He is the New York City editor of the New Art Examiner.

(Top) Tom of Finland, Untitled, 1979. graphite on paper, 21 7/8 x 17 1/8 x 1 1/2 inches (framed). Photo:Jeff McLane, courtesy of David Kordansky Gallery. (Bottom) Kake vol. 22–Highway Patrol, 1980. Pen and ink on paper , one of 20 parts, each: 18 3/8 x 14 7/8 x 1 1/2 inches (framed). Photo: David Kordansky Gallery.

%201974%20rgb.jpg?crc=8713517)

Tom of Finland, Untitled (from “Setting Sail”), 1974. Graphite on paper, (framed) 17 58 x 14 x 1 1/2 inches. Photo: David Kordansky Gallery, NYC.

Tom of Finland, Untitled, c. 1966–1990. Graphite, marker, guache and mixed media on paper, (framed 16 3/8 x 13 7/8 x 1 1/2 inches. Photo: David Kordansky )Gallery, NYC.

%20rgb2-crop-u186310.jpg?crc=4207218885)

Felix Gonzalez-Torres, “Untitled" (Public Opinion), 1991. Black rod licorice candies in clear wrappers, endless supply. Overall dimensions vary with installation; ideal weight 700 lbs. Photo: David Zwirner Gallery.

Felix Gonzalez-Torres, “Untitled" (Sagitario), 1994–1995. Medium varies with installation, water, 24 x 12 feet overall; two parts 12 feet in diameter each. Photo David Zwirner Gallery.

(Below) Felix Gonzalez-Torres (installation view), “Untitled,” 1994–1995. Mixed media; dimensions vary with installation. Photo: David Zwirner Gallery.