“Tongue and Nail”

at Iceberg Project, Chicago

by Annette LePique

In Iceberg Projects’ spring show “Tongue and Nail,” artist Tarik Kentouche’s sculptures of Carlo Mollino’s “Gaudi” chair inundated a gallery antechamber with surprising sinew and reaching, deceptively delicate, movement. Kentouche’s sculptures, in all their exoskeletal pleasures, brought to mind the chair-like apparatus at the heart of David Cronenberg’s film Crimes of the Future. In the film, humanity en masse seems to be changing; some can no longer eat food (instead hungering for plastic), feel pain, or have penetrative sex. How we relate to one another and how we relate to our surroundings is initially framed as inextricably, irreversibly alien. We soon align ourselves with one of the story’s protagonists, Saul. Saul is an artist who cannot feel pain and has intense difficulty chewing, swallowing, and digesting food. In order to eat, Saul utilizes a LifeFormWare digestion-assistance chair—a tendon-snapping machine that becomes both a part of his body, tongue and teeth, but remains something other, different than meaty gums and slick esophagus. The LifeFormWare chair and Saul are thrown into a liminal bond where the demarcations of Saul are blurred, the boundaries between his inside and outside merged.

Yet, isn’t that alienation, the sheer strange luck of inhabiting a body, the defining condition of flesh? Isn’t the very fact that flesh degrades, that it’s ephemeral, penetrative and porous, is what makes it possible to form the vocabulary of one’s existence?

Curated by John Neff and Daniel Berger, “Tongue and Nail” embraces the permeability between the horrors and sublime experiences of occupying a body, those sensations frequently being one and the same—the sensations that Cronenberg explores in his films. Taking the tongue as their touchstone from a viewing of Kate Bawden’s video piece Tongue Tie (2022) (alongside Kentouche’s sculptures), Neff and Berger assembled a cadre of artists—including Doron Langberg, Le Hien Minh, Jeff Prokash, David Sprecher, Tom of Finland, and Maggie Wong—whose work both expands and contracts notions of what a tongue is, to explore what it means to live within, to move within, to be a person within flesh.

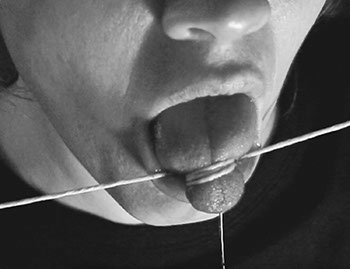

Bawden’s Tongue Tie, a one-minute video piece, is one of the show’s catalysts. The work is projected on the gallery’s back wall, easily the first piece to catch one’s eye upon entering the exhibition. The video opens on a close up shot of a tongue. The tongue, bound by vertical and horizontal strands of twine, occupies the center of the filmic space, and the events of the film occur entirely in silence. The camera’s lens stays trained on this tongue, while the individual who possesses said tongue pulls tighter and tighter on the strands of twine. Their hands remain slightly off screen, as does the face of the individual. All viewers see throughout the video is this tongue; all we’re asked to see is this tongue. Rivulets of spit drip off the tongue as the twine contorts it into shapes both alien and familiar. The flesh is bound into pockets of soft, wet, meat.

In Bawden’s artist statement they write that they have an interest in interrogating the relationship between the body, time, and memory in the aftermath of traumatic experiences. There’s an implicit understanding that when a tongue is tied, it cannot aid in the act of speech. A subject’s ability to speak, to form consciousness through language, is hampered or otherwise slowed down. In Greek myth, Philomela is a young noble woman who was raped, and her tongue cut out by her assailant. Yet, there are many ways to speak, to communicate pain, pleasure, and the untold varieties of sensation that lie between the two. Philomela wove her story and sent the resulting tapestry to her sister to identify her attacker and seek revenge. I tell this story alongside Bawden’s artist statement as there is power in binding oneself, in giving up power freely on one’s terms. The body once again becomes one’s own, a teller of stories and those stories of infinite, untold variety. Such is the mark, the burden, the gift of being human.

The variety of pieces included in the show are wide ranging in material and subject matter. Some are non-representational, like Le Hien Minh’s wall sculpture, while others like Langberg’s paintings or Tom of Finland’s sketched scenes, portray couples in varying states of passionate embraces. There’s a unifying interest in what it means to be present in a body capable of giving and receiving pleasure, pain, and care. This is an investigation that transcends differences in material and form to make generative use of the unavoidable frictions that occur in such endeavors. For the tongue, the body, and the contours of one’s personhood are also landscapes of those friction-filled liminal spaces. It’s there you might not only find relief, but also understanding, a sense of self.

David Sprecher and Jeff Prokash, Well, 2023. Plaster, parakeet feather. Photo: Iceberg Projects.

Annette LePique is an arts writer. Her interests include the moving image and psychoanalysis. She has written for Newcity, ArtReview, Chicago Reader, Stillpoint Magazine, Spectator Film Journal, and others.

Kat Bawden, Tongue Tie, 2022. Video (1:00 min). Photo: Iceberg Projects.

Tarik Kentouche, Avantgard, 2022. Resin, painted wooden pearls, metal joints, 16” x 16” x 32” inches, approximately. Photo: Iceberg Projects.

Le Hien Minh, Ornamentalism, 2022 – ongoing. Traditional Vietnamese handmade Dó paper, wood, acrylic, 28 x 8 x 11 inches. Photo: Iceberg Projects.

Doron Langberg, Zach and Craig #4, 2019. Oil on linen, 61 x 45.7 inches. Photo: Iceberg Projects.