The World to Come: Art in the Age of the Anthropocene

by KA Letts

The day after I saw the University of Michigan Museum of Art’s current exhibit “The World to Come: Art in the Age of the Anthropocene,” I saw this headline on the front page of the New York Times: Report Details Global Shrink in Biodiversity. It was accompanied by images of bleached coral and strangled sea turtles. On the same page I saw a picture of Lady Gaga in black lingerie on the steps of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, vamping for the cameras on the occasion of the annual Met Gala.

I like to think I would have been shocked by this juxtaposition of the catastrophic and the trivial before I saw the exhibit, but I’m not sure. We live in an age of distraction and it’s easy for us humans—famous for our short attention spans—to lose sight of the enormous challenge posed by global warming. “The World to Come” makes the point, devastatingly, incontrovertibly, unforgettably, that we live in an era of rapid, radical and irrevocable ecological change.

The show, curated by Kerry Oliver-Smith of the Harn Museum of Art at the University of Florida, hits you right between the eyes with images of humanity’s effect on the natural environment, and it keeps on hitting. Sections of the show are broken down into categories such as Deluge, Consumption, Extinction, Imaginary Futures and the like, categorizing the environmental outrages to make the enormity of the subject (and the size of the show) comprehensible.

It’s ironic that an exhibit devoted to destruction and climate disaster should be so very beautiful but … well, there it is. Photography and video provide the lion’s share of the selections, although more traditional modes of expression, such as fiber art, ceramics, drawing and bronze sculpture are also represented. Even these more handcrafted artworks, however, are smoothly textured and coolly dispassionate. As an example, the Japanese ceramic artist Kimiyo Mishima has meticulously crafted trompe l’oeil stoneware objects that mimic the crushed soda cans that clog landfills and waterways. Likewise, the diminutive and ghostly needlepoint images of American artist Noelle Mason record a different, more human, ecological cost, depicting infrared images of undocumented climate refugees crossing the U.S.-Mexican border. William Kentridge’s procession of bronze figures, part man and part machine, add a welcome touch of the artist’s hand to the smooth aesthetic of the show.

Many of the artworks, though excellent, come at the subject in a way that has lost its ability to shock; aerial shots of housing subdivisions, and feedlots with their bloated lagoons are very much in the public domain now. The proliferation of environmental atrocities has made it almost too easy to capture indelible images of the devastating effect of our species on the natural world.

Chinese artist Liu Bolin’s photograph of a sooty figure, nearly invisible against a background of piled-up coal, comments on the environmental and human cost of coal extraction. Chris Jordan’s photo of the remains of a juvenile albatross, its stomach filled with plastic waste, illustrates the damage to wildlife from our thoughtless consumption of disposables. Mary Mattingly has created a lovely and telling nude photo of herself lying prostrate under a bundle made up of her household possessions. All these images are beautiful and memorable, but risk becoming the environmental equivalent of “ruin porn”, aestheticized portraits of ecological carnage.

Liu Bolin, Hiding in the City, No. 95, coal pile, 2010, chromogenic print on plex. Photo courtesy of UMMA.

The portraits of people displaced from their flooded homes by Gideon Mendel in his series Drowned World, document a phenomenon that has become sadly routine. The photographs are saved from banality by the artist’s connection to the English, Haitian and Indian subjects. They stare into the camera, undone by the destruction of their homes, geographically separated from each other, but united in their common predicament.

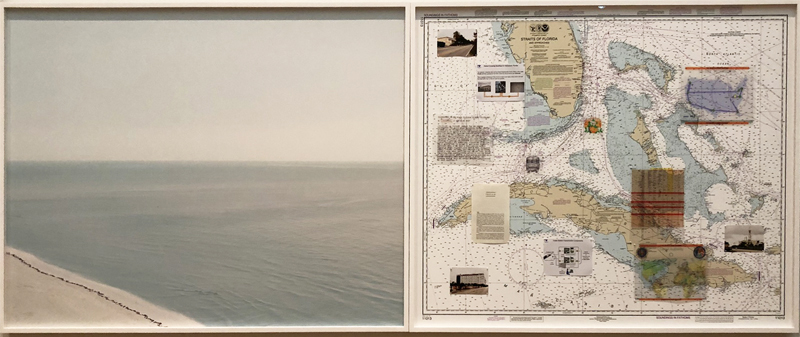

Some of the most effective works in “The World to Come” have found new and inventive ways to change our minds about humanity’s relationship to nature. Two images by Trevor Paglen come to mind. A panoramic photograph of a scenic beach near Miami Beach, Florida, is paired with an adjacent map of the same area. The map shows underwater NSA-tapped fiber optic cables, sea routes and other evidence of human navigation, products of human technology that are invisible to the human eye. A cryptic and open-ended video by the Portuguese artist Pedro Neves Marques is entitled The Pudic Relation of Machine and Plant. In it, a robotic arm is seen reaching for a sensitive plant, which recoils at its touch. The relationship of plant to robot invites speculation as to present and future interactions of technology and the natural world.

Gideon Mendel, Drowning World Series, 2008-2014, chromogenic prints. Photo courtesy of UMMA.

Trevor Paglen, NSA Tapped Fiber Optic Cable Landing Site, Miami Beach, Florida, United States, 2015 chromogenic print and mixed media on navigational chart. Photo courtesy of UMMA.

The 35 global artists represented in “The World to Come” have persuasively made the case that climate change is a worldwide existential threat. The introductory statement in the gallery states that “Contemporary art plays a crucial role in negotiating the rapid changes observed during the Anthropocene by reconceptualizing the traditional ways we think about nature and culture.” I hope this is true, but the question follows: what should we do now?

Originally published in AADL Pulp, May 15, 2019.

“The World to Come: Art in the Age of the Anthropocene” will be on view in the A. Alfred Taubman Gallery at UMMA until July 28, 2019. For more information, go to https://www.umma.umich.edu/exhibitions/current.

K.A. Letts is a working artist (kalettsart.com) and art blogger (rustbeltarts.com). She has shown her paintings and drawings in galleries and museums in Toledo, Detroit, Chicago and New York. She writes frequently about art in the Detroit area.