“The First Homosexuals”: The Interplay of Art and Language

by Michel Ségard

Wrightwood 659, once again, presents us with a thought-provoking exhibition on the history and role of homosexuality in our culture. In 2017 the Alphawood Foundation presented Art AIDS America Chicago. A year later, Wrightwood 659 gallery was completed, and in 2019 the exhibition “About Face: Stonewall, Revolt, and New Queer Art” was mounted there, curated by Johnathan Katz. Now in this space Katz has staged a fresh show, “The First Homosexuals: Global Depictions of a New Identity, 1869–1930,” an exhibition that explores the art-historical role the term “homosexual” has had since it was coined by the Hungarian writer Karl Maria Kertbeny in 1869. And this exhibition is just a preview of a much larger offering on the same topic scheduled for 2025.

This exhibition is not about the art per se. The aesthetics of any given piece play a very minor role here. In this show, we are looking at how the term “homosexual” affected how we interpreted the art that was produced after its incorporation into our language. The thesis of the exhibition is that, before 1869, the concept expressed by the word “homosexual” was an adverb, describing something someone did. After the term itself was coined, the concept became a noun and began to describe someone “indulging” in a same-sex lifestyle. Because this show only includes art produced up to the 1930, it does not reflect the aesthetics and cultural attitudes of our contemporary society.

Structurally, “The First Homosexuals” is organized into nine sections, each addressing a particular aspect of the homosexual experience and highlighting a particular subset of imagery with homosexual undertones or content, some of it explicitly depicting sexual acts. Most of the work is from the United States and Europe, but some comes from China, Japan, and other Asian countries.

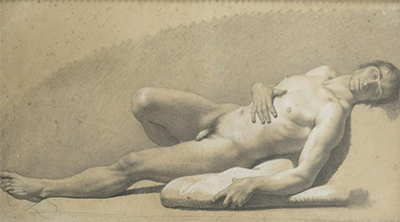

Before “Homosexuality” looks at how cultures around the world perceived homosexual acts and desires. There are three pieces from late 18th- and early 19th-century Europe that portray same-sex relations between men in which one is passive and plays the feminine role. This view of homosexual relations between men dates back to ancient Greece, where no stigma was attached to it. It was considered a natural part of life. Academy of a Reclining Man embodies the European stereotype. In this drawing by an artist in Jacque Louis David’s circle from around 1790, the full-frontal figure is reclining, seemingly asleep, and totally vulnerable, yet endowed with a virtually perfect physique. Also in this section is a Japanese scroll from around 1850 that depicts sexual acts between an older female attendant, a samurai warrior, and a Buddhist monk in various combinations. No sexual act is preferred or impugned. Also included are a piece from China and one from early 19th-century Japan that shows two men engaging in sodomy. It is clear that, in the East, same sex activity was fully acknowledged and practiced, also seemingly without social stigma. It is disappointing that, effectively, Before "Homosexuality" had only three works from the West. Homoerotic art was produced in the West at least since the Renaissance, with Michelangelo and Caravaggio producing works that lend themselves to such interpretation. It would have been helpful if a few other pre-19th-century examples had been included to round out what had gone before in Europe. It is interesting to note that all the Asian pieces showed overt sexual acts, while the European pieces only depicted objects of desire.

French school, circle of Jacques Louis David, Academy of a Reclining Man, c. 1790, Charcoal and

white chalk highlights on paper, Michael Sodomick Queer Art Collection. Photo: Wrightwood 659.

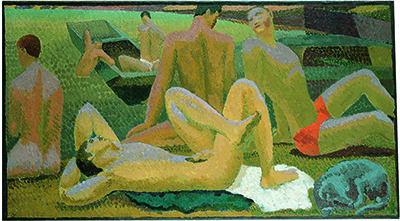

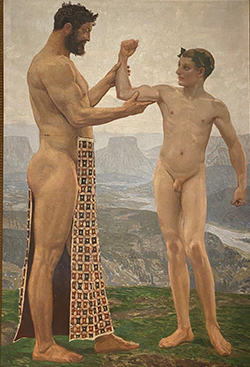

The next section in the exhibition is Archetypes. In a way, this section codifies the stereotypic, neoclassical depiction of male homosexuality in late 19th-century art—an alluring youth being admired by an older man, as seen in Sascha Schneider’s 1904 large oil Growing Strength. In some circles, that stereotype lingers to this day. But there is an evolution in male imagery, mostly in the decades between the start of World War I and the mid-1930s. The male object of desire, although young and handsome, becomes admired by other men of the same age, as seen in Duncan Grant’s Bather by the Pond (1920–21) or Eugène Jansson’s Bathhouse Study. We see similar scenarios a little later in the works of Paul Cadmus.

Duncan Grant, Bathers by the Pond, © Estate of Duncan Grant. All rights reserved, DACS, London / ARS, New York. Photo: Wrightwood 659.

The next section, Desire, illustrates the difference in sexual imagery between the West and Asia. The wall panel for this section describes it best:

"In this section, you will notice significant distinctions between Western and Eastern imagery in relation to desire. While Western art sought to seduce its viewers’ fantasies with highly suggestive imagery, only rarely was sexual penetration depicted, and never in a fine art context. This gulf between art and pornography in the West…makes little sense in an Asian context where sex was understood as a part of life. It was only after Japan opened to the West in 1869 that it began to police homosexual representation—not because the dominant culture objected to it, but because they feared the West would find it distasteful, potentially damaging Japan’s overtures to Europe and the Americas."

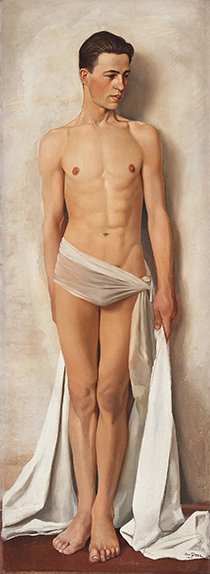

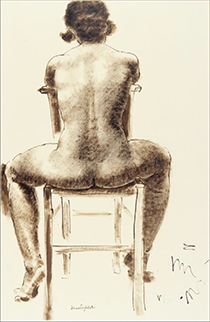

But another phenomenon begins to appear in this section. Two European pieces that were not frontal, Konstantin Somov’s Standing Male Model from Back (1896) and Jane Poupelet’s Nu de dox à califourchon sur une chaise (Nude from the back astride a chair) (1906), suggest more than mere physical attraction. In these pieces, desire becomes more directed to the whole individual by virtue of not seeing their external sexual characteristics. It becomes more “intellectual” in nature, in contrast to the introductory piece to this section, Owe Zerge’s Model Act (1919), which is primarily erotic and highly romantic.

Appropriately following is the section Couples. Here we are presented with portraits of artists’ romantic partners. Of the 11 paintings in this section, only three are of couples together. The most noteworthy is Louise Abbéma’s painting Sarah Bernhardt et Louise Abbéma sur un lac (Sarah Bernhardt and Louise Abbéma on a lake) from 1883. In this painting, Bernhardt is seen lounging at one end of a boat, while Abbéma, her companion, stands at the other end, dressed in mannish clothes. As the wall text states, “This is an example of a painting speaking to two audiences at once. For most viewers, it was a portrait of Bernhardt at leisure, while for a few, it was a portrait of domestic intimacy.”

Another interesting painting in this section is Frances Mary Hodgkins’s Friends (Double Portrait) [Hannah Ritchie and Jane Saunders], done between 1922 and 1925. It is the second of only five paintings that actually show couples. (Two of them are small images from China and Japan that show couples in coitus.) In Hodgkins’s vaguely Matissian painting, the partners in the couple are side by side but not engaged with each other, each looking in a different direction. This painting also chronicles an exception to 20th-century heteronormative society in the West. Female same-sex couples were allowed to exist publicly—not so for males.

-crop-u171130.jpg?crc=3890758564)

Frances Hodgkins, Friends (Double Portrait) [Hannah Ritchie and Jane

Saunders], 1922-1923. Oil on canvas, 24 x 30.3 inches. Hocken Collections,

Uare Taoka o Hākena, University of Otago. Photo: Wrightwood 659.

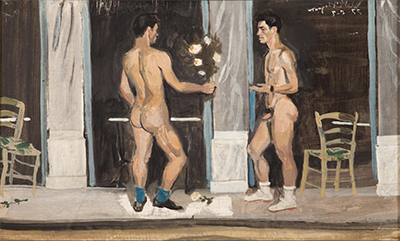

The only paintings addressing male couples are the ones from China and Japan, mentioned earlier, and Alastair Cary-Elwes’s Rupert Bunny from 1887. Cary-Elwes and Bunny were both artists from affluent families who shared a studio in Paris. Bunny was married to what we call a “beard,” a woman who is married to a homosexual man for appearances. In this painting, Bunny is depicted playing the piano in a serious, attentive mood. There is no hint of Cary-Elwes in the painting. Male homosexual couples are extremely rare in Western art. Yannis Tsarouchis did a few; The Bouquet from 1955 shows one nude man handing a bouquet of flowers to another nude man. However, note that it was done in the mid 1950s, much later than the timeframe of this exhibition. Meanwhile, the book “LOVING: A Photographic History of Men in Love, 1850s–1950s” (5 Continents Editions, 2020) has hundreds of photographs of male couples. But these photographs are snapshots from daily life and not normally considered works of art.

The exhibition continues with Pose. Today, when we hear that word, we think of Madonna and voguing. Its meaning within the context of this exhibition is not that far removed. The section starts with the Mexican painter Roberto Montenegro’s Retradto de un anticuario o Retrato de Chucho Yeyes y autorretatron (Portrait of an Antiquarian or Portrait of Chucho Yeyes and a Self Portrait), painted in 1926. The first thing one notices is the pursed lips of the subject and the “limp-wristed” hand gestures. In this portrait, the subject’s sexuality is being exposed for all who know how to read the code. As modernist as this work is, the painting pays homage to the past by borrowing from Jan van Eyck’s Arnolfini double portrait; the portrait of Montenegro is a reflection in the glass globe on the desk.

In addition to exposure, a pose can also indicate overwhelming confidence, even arrogance. Much of these characteristics are evident in noted lesbian artist Florence Carlyle’s Self Portrait of 1901. From Ontario, she studied painting in Canada and France and worked mostly in an impressionist style. As the exhibition wall label states, her favorite subject matters were “domestic, feminine spaces, focusing on the intimate lives of contemporary women, including her lover, Judith Hastings.” Carlyle moved to Crowborough, England, around 1903 and spent the rest of her life there with Hastings.

The next section, Between Genders, is of commanding political interest for the LGBTQ+ community today. As the section’s wall text states, “While the term ‘homosexual’ implies a union of people of the same gender, it obscures the difference between one’s biological sex and one’s gender identity, two terms we are today coming to better understand and embrace as part of the trans revolution unfolding around us.” This section looks at cross-dressing (drag) and what we now sometimes call gender bending.

The section starts with a traditional cross-dressing example. Henri Legludic’s 1896 book Notes et observations de médicine légale published the account of Arthur W., who preferred to go by the name The Countess. The wall label summarizes Arthur’s life from the time he became the “mistress” of a wealthy aristocrat at 13 to his later years as a sex work on the streets.

This section also includes a film short by August and Louis Lumière, Danse Serpentine [I] from 1897. It shows Loïe Fuller doing her famous Serpentine Dance, along with a drag version by the Italian actor Leopoldo Fregoli. Nearby are two photographs from 1903 of two Black actors (Charles Gregory and Jack Brown), with Gregory in drag, dancing the cakewalk. There is also a digital reproduction of a film by the Lumière brothers of Gregory and Brown dancing,

Gregory again in drag. These pieces demonstrate the beginning of the acceptance of cross-dressing in modern Western society. (It must be noted that in 16th and 17th century European theater, female roles were played by men in drag.)

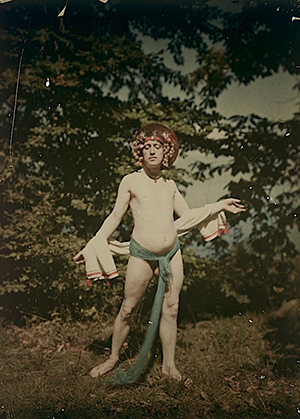

But there is a more subtle development taking place around the early 20th century. Some artists are feminizing normally male subjects in their work. Two examples in this show are Jan Zrzavý’s St. John, Disciple whom Jesus Loved (1913) and František Drtikol’s untitled photograph of a young male youth. Drtikol feminizes the youth by the use of light and shadow to emphasize the boy’s androgyny. As a result, the image appears to oscillate between genders. The acceptance of gender fluidity has grown in modern times to include gender-neutral individuals who dress in a gender-mixing and sexually ambiguous way, along with the use of the gender-neutral pronouns they, them, their, and ze/hir.

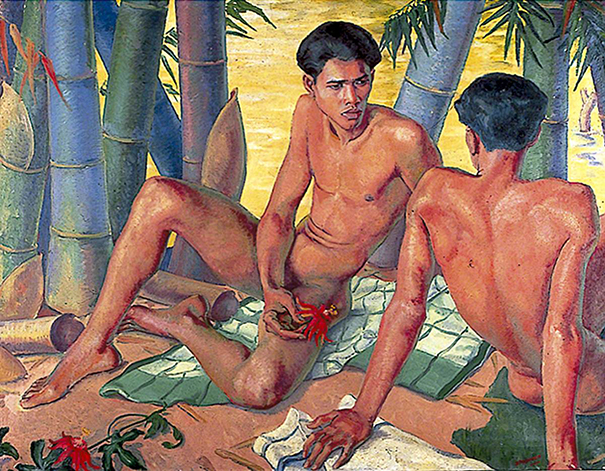

Colonizing, the next section of the exhibition, addresses the impact of European colonization on the changing attitudes regarding same-sex relationships and eroticism. From the wall text introducing this section:

"While a number of indigenous cultures carved out what was often a respected place for same-sex sexuality, “homosexuality” came to be imposed on these cultures, investing them in Western ideologies that literally rewrote indigenous relationships to their own histories and social practices. This ideological colonialism was so successful that some countries that once accepted same-sex relations now harshly punish them according to the dictates of colonial-era law, despite being long-liberated from European colonizers."

What is not stated in this wall text, but implied elsewhere, is that much of the changes were based on economic grounds—in other words, the willingness to alter one’s cultural traditions for economic gain through trade.

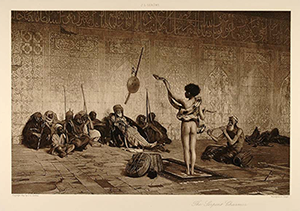

The Serpent Charmer, a photogravure after the famous painting by Jean-Léon Gérôme, depicts a naked young boy “handling” a snake while being looked on by older men. Clearly he did not need to be naked to work with the snake. Here we are exposed to the double standard then prevalent in the Arabian Peninsula. Mature men were allowed to “enjoy” young boys as long as they had a heterosexual relationship with a wife, an attitude with roots in classical Greece. The “I’m not gay as long as I am the top” attitude still survives today in some parts of the world.

The most striking piece in this section is David Paynter’s large painting L’après-midi (c. 1935). Done in a vaguely Gaugin-like style, the painting depicts two naked young men “exchanging glances” (as Sinatra once sang). The one facing us holds a flower with a conspicuous stamen—in this case, a phallic symbol. There is not only the sense of desire on the face of the youth holding the flower but also an undertone of melancholy. Same-sex relationships in Ceylon where Paynter lived (now Sri Lanka) were not originally taboo. But, as the wall text to this painting states,

David Paynter, L’aprè-midi, 1935. Oil on canvas, 39 x 48 inches. Brighton & Hove Museums. Photo: artuk.org.

"British colonial rule criminalized homosexuality in South Asia in 1861, effectively toppling its acceptance among indigenous populations. As both an indigenous and European artist, Paynter occupies an in-between subject position, shedding light on the colonial interactions that defined the development of sexual politics in modern South Asia."

While containing only half a dozen pieces, this section turns out to be, for me, one of the more politically powerful, showing how the European official policy of Victorian frigidity affected the cultural values of the parts of the world that it colonized.

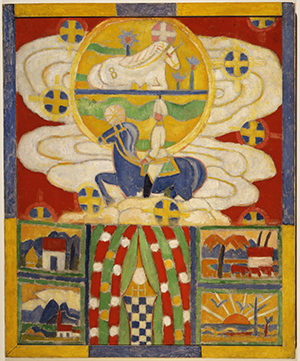

The wall text for Public/Private defines this section in these words: “Given the privatization of homosexual lives, it is perhaps not surprising that a number of artists sought to confuse or repudiate the distinction between public and private. For these artists, homosexuality and the realm of public life are not divorced, and they worked to expose a queer viewpoint on dominant culture.” There are two pieces in this small section that spoke to me. The first is Marsden Hartley’s Berlin Ante War from 1914. Hartley was enamored of a German officer, Karl von Freyburg. His beloved died in October 1914, during the early part of World War I. Hartley’s work is an elegy in oil; the bottom three panels of the painting depict an idealized prewar Germany, which Hartley admired, while the upper panels show von Freyburg ascending into heaven on a horse, surrounded by Greek crosses. This is one of the very few works in the show that directly address the love of another rather than the desire for someone’s body. By contrast, the painting of Bernhardt and Abbéma in a boat have the two far apart, and they don’t even look at each other. It is a work primarily about their homosexuality, not their love.

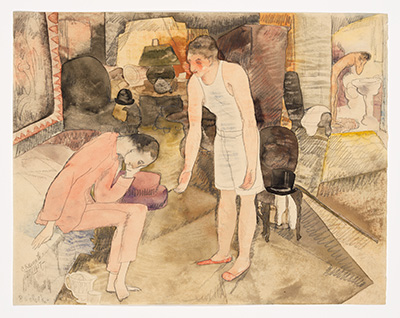

The other painting in this section that impressed me was Charles Demuth’s 1917 watercolor Eight O’Clock (Early Morning). Demuth is best known for his precisionist paintings of industrial scenes and his iconic I Saw the Figure 5 in Gold from 1928. But there is another side to Demuth. He was openly gay and had a lifelong romantic relationship with interior decorator and stage designer Robert Evans Locher. Eight O’Clock (Early Morning) is a very subdued sample of his work addressing his homosexuality. His Dancing Sailors, a watercolor and pencil piece from 1918 (not in the exhibition), shows sailors dancing, two with each other and two looking one another over, and another piece from 1918, Turkish Bath with Self Portrait (also not in this show), has flooded the reproduction market. Other Demuth drawings and watercolors even cross over into pornography.

(Left) Charles Demuth, Eight O'Clock (Early Morning), 1917, Watercolor and graphite pencil on paper, 8 1/16 × 10 5/16 inches. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. Photo: Wrightwood 659.

(Left) Charles Demuth, Eight O'Clock (Early Morning), 1917, Watercolor and graphite pencil on paper, 8 1/16 × 10 5/16 inches. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. Photo: Wrightwood 659.

These two artists had a very different response to their homosexuality. Hartley was firmly in the closet, but Demuth was as out as you could be for his time.

The last segment is called Past and Future. This section concentrates on the Elisarion, a social movement started in Switzerland in 1926 by the German artists Elisàr von Kupffer and his partner Eduard von Mayer. They transformed a Swiss villa into a temple/museum formally named Sanctuarium Artis Elisarion. The goal was to embrace homosexuality and restore its rightful place in history, and the Elisarion was sought out by men from all over Europe. Von Kupffer and von Mayer even invented a new religion called Clarism. It was a utopian doctrine that encompassed theosophy, but with a German flavor and fascination with ancient Greco-Roman civilization. The 15 prints from the Getty Research Institute in this exhibition reflect Clarism’s attempt to create an androgynous ideal. One print shows a room in the villa that had a mural depicting this idealized androgyny. The other prints mostly show von Kupffer posing nude in a variety of “classical” positions.

(Left) Elisàr von Küpffer, the entrance to the cyclorama at Sanctuarium Artis Elisarion. (Right) Von Küpffer striking a neoclassical pose. Photos: ultrawolvesunderthefullmoon.blog

Gerda Wegener, an artist from Denmark, presents the lesbian ideal in her painting Venus and Amor. In this picture, Cupid is gender queer, having both male and female attributes, and Venus, who is helping Cupid draw his bow, has somewhat masculine body proportions. Also in this section is Finnish artist Magnus Enckell’s Man and Swan. In the Greek myth, Zeus turns himself into a swan and rapes Leda. There is another classical story of Zeus turning himself into an eagle to rape the youthful Ganymede. Enckell merges the two myths, and the swan (Zeus) is thwarted by Ganymede as he asserts his right to his own body.

.png?crc=4065909219) Gerda Wegener, Venus and Amor, (not dated), Oil on canvas, 35.4 x 49.2 inches. The Shin Collection, New York, Image Courtesy of Shin Gallery,

Gerda Wegener, Venus and Amor, (not dated), Oil on canvas, 35.4 x 49.2 inches. The Shin Collection, New York, Image Courtesy of Shin Gallery,

New York.

This section demonstrates how homosexuality was idealized by artists emulating classical forms. What has not yet fully evolved is a legitimacy that can survive in present-day society. So, homosexuals, be they anyone in the spectrum of the LGBTQ+ community, sometimes still have to assume roles or characters and cannot truly be themselves.

The exhibition closes with a video clip of a bare-breasted Josephine Baker dancing the Charleston and making her famous cross-eyed faces while holding one finger from her hand on top of her head. This image was disturbing in its self-deprecation. Her most “famous” dance was the banana dance. It was explicitly sexual—these days, we would equate it to twerking. Yet Baker was famous in France as a performer and a resistance fighter during World War II. She became a French citizen and was awarded the Resistance Medal and the Croix de Guerre and named a Chevalier of the Légion d'honneur by Charles de Gaulle. Although she was married four times, according to her adopted son Jean-Claude, she had numerous lesbian relationships, including with the French novelist Colette and the American Black expatriate singer Bricktop.

Homosexuals needed to “act” in order to be accepted in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. They were either in the closet or, sometimes, inhabiting a grotesque caricature of the person they wanted to be. This dilemma still exists, albeit in a much diminished form. And this exhibition brings home the continuing international struggle for acceptance and a place to fit in socially. Today, it is somewhat easier, but the struggle for authentic self-definition of homosexuals continues.

Michel Ségard is the Editor in Chief of the New Art Examiner and a former adjunct assistant professor at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. He is also the author of numerous exhibition catalog essays.

Owe Zerge, Model Act, 1919. Oil on canvas, 53.1 x 19.7 inches. Private Collection. Photo: Wrightwood 659.

Sascha Schneider, Growing Strength, 1904. Oil on canvas. Photo: glreview.org

Jane Poupelet Nu de dos à califourchon sur une chaise, 1906. Sepia on paper, 23.8 x 15.3 inches. Photo: centrepompidou.fr.

Louise Abbéma, Sarah Bernhardt et Louise Abbéma sur un lac, 1883, Oil on canvas, 63 x 82.6 x 1.2 inches (framed). Collections Comédie-Française. Photo: Wrightwood 659.

Janis Tsarouchis, The Bouquet, 1955. Mixed media on canvas laid on board, 8.9 x 14.4 inches. Photo: bonhams.com.

Roberto Montenegro, Retrato de un anticuario o Retrato de Chucho Reyes y autorretrato, 1926. Oil on canvas, 40.4 x 40.4inches. Colección Pérez Simón, Mexico. Photo: Wrightwood 659.

Untitled [Two Black actors (Charles Gregory and Jack Brown), one in drag, dance together on stage], c. 1903, Process print with watercolor, 5.5 x 3.5 inches. Wellcome Collection. Photo: Wrightwood 659.

The Serpent Charmer, Galerie Goupil & Cie, after Jean-Léon Gérôme, c. 1894. Photogravure.

Photo: Wrightwood 659.

Marsden Hartley, Berlin Ante War, 1914, Oil on canvas with painted wood frame, Columbus Museum of Art, Ohio: Gift of Ferdinand Howald. Photo: Wrightwood 659.

(Above) Charles Demuth, Dancing Sailors, 1917. Watercolor and pencil, 8 1/16 x 10 1/8 inches. Cleveland Museum of Art. Photo: clevelandart.com

Magnus Enckell, Man and Swan, 1918. Oil on canvas,

42.5 x 31.5 inches. Serlachius Museum Gösta, Finland.

Photo: advocate.com.

Josephine Baker dancing the Charleston, date unknown. Still from the video Dancing Up a Storm on youtube.com.