“On the Road”

“We had longer ways to go. But no matter, the road is life.”

Sal Paradise

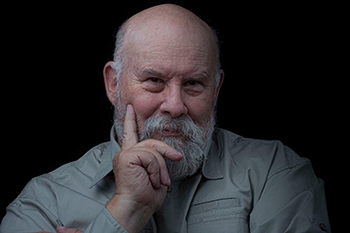

An Interview with Ted Stanuga

by Neil Goodman

There is a certain restlessness that personifies the paintings of Ted Stanuga. From the early representational works, through the later abstractions, there is a speed and intensity to the painting, where act and thought seem perpetually in motion. Like the characters Dean and Sal from Jack Kerouac’s book “On the Road,” the journey is the destination, with an endless horizon that forever remains in the distance. This is the pleasure of Ted’s paintings, a thin line where beauty is tenuous, and where the work travels through the rivers and valleys of generations before yet emerges with a voice distinctively his own.

Artists know each other through friendship and through their work. In most ways, we are each other’s first and perhaps most important audience, as our words of encouragement and questioning become the foundation of an ongoing dialogue that becomes part and parcel of the creative process.

Such is the case with Ted Stanuga. Upon my moving to Chicago in 1979, we shortly found ourselves as neighbors in Pilsen. Ted was working at the time as the crew manager at the MCA, and I had recently completed my MFA at the Tyler School of Art in Philadelphia. Although our initial interests and experiences were quite different, the frequency of studio visits as well as a shared artistic community created both collegiality and comradery, as we were both beginning our careers. For more than forty years, our paths have crossed in any number of ways, and we have continued to stay abreast of each other’s work through studio visits, exhibitions, emails, and exchanged images.

Ted is at a turning point. Facing stage four prostate cancer, this dialogue is my opportunity to publicly extend a conversation that has been with us for more than four decades. This interview is as follows:

Neil: You were born in San Diego in 1947 and attended high school there. After high school you left and worked at the Anaconda zinc plant in Montana, then was drafted in 1967 and joined the marines. This was quite an unconventional start. What sparked your early interest in becoming an artist?

Ted: In high school, three teachers, Enid Miller for art, Ernie Neveu in track and field, and Harris Teller in Life Studies, were formulative to my early artistic education. After the Marines and returning to Montana, I enrolled in The College of Great Falls, (a small liberal arts college) and studied for three years with the abstract painter Jack Franjevic. Jack had attended the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC) as well as lived in New York City. Jack then helped me get into the SAIC. That was 1973.

Neil: You attended SAIC for several years. This was at the height of the “Hairy Who.” What was that like, and who were the teachers that influenced you at that time? It is also quite interesting, that as the artworld has changed so dramatically, we look upon that period as perhaps our history of coming of age in Chicago. But for the generations that have followed, it is more of a distant memory and part of a bygone era.

Ted: Not many teachers were interested in my abstract paintings when I arrived at SAIC. The exception was Tom Kapsalis who was very challenging and looked carefully at my drawings and paintings. My studies were focused on work both with Tom as well as the printmaking department. It was in printmaking classes that I began to explore images of different kinds: portraits of my parents, dogs, landscapes, still life.

%20rgb.jpg?crc=3926137497)

Neil: You worked as a printmaker at Jack Lemons studio (Landfall Press) for a number of years before working at Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA). What was that like?

Ted: I got an opportunity to work at Landfall Press through a ten-week grant. After the 10 weeks I was offered a position as his assistant. Jack was tough but very kind and directed me both conceptually and technically. The first artist I met was Claus Oldenburg, the first edition was his “Bat Spinning at the Speed of Light.” When I left, I realized that I wanted to do my own paintings, and that I was not a lithographer.

Neil: You worked at the MCA during the Mary Jane Jacobs years. What shows did you install?

Ted: Working at the MCA was an amazing experience. Nam June Paik, Phillip Guston, Malcolm Morely, “Kick out the Jams,” Magdalena Abakanowicz, to name a few. I learned how to work with a crew, some of whom have become lifelong friends. The shows came often and demanded much from the staff and crew.

Neil: Your first Chicago show was at Karen Lenox gallery in 1992. I remember the paintings of semi-rabid dogs. In some sense they might have been working out the violence in the military. They bring me back to the Cormac McCarthy novels, as images of a ravaged world. In retrospect, as your work has changed considerably, how do you feel about that body of work some forty years later?

Ted: As for that work, some of the original concepts continue to creep into the work especially in the last two years. You are correct in seeing that the Vet experience contributed to those early works. The edges are no longer as sharp but still linger in the later work, however less overtly.

Neil: We all lived in Podmajersky rentals around 18th and Halsted in the 1980’s in Pilsen. The neighborhood was bereft of most amenities, yet for many of us, it was an introduction to a community of artists. Who do you remember from those years, and what was that community like for you?

Ted: I’ll begin with Lupus and Peter Rosenbaum and their “Missouri Gallery”, located in a loft building in Pilsen. They gave me a drawing show and a show of my still life paintings and along with Linda Lee, they were very close friends. For years we shared meals, trips, shows, and many Thanksgiving dinners. You were next door as was the ceramicist, Robert Rosenbaum. Watching both of you developing as artists influenced me profoundly.

Neil: Shortly after the Karen Lennox years, there seemed to be a large disjunction in your work. The Phillip Guston show at the MCA seemed to be a critical juncture for many Chicago artists, as he pointed to a new form of figuration. In many ways it had never really left the Chicago Art World. Did these exhibitions factor into your work? Also, there seems to be the beginning rumblings of your interest in Picasso, Braque, and DeKooning, as well as the color field painters—perhaps Joan Mitchell. When I look at your work, I see how much you admire other artists. I move through Conrad Marca-Relli, Paul Cezanne, Markus Lupertz, Mark Tobey, Jackson Pollack, Mark Rothko, to name a few. That is one of the things I admire about your paintings, they have a certain empathy and love of the tradition. Equally, as an active participant in the Chicago Art World, were there other Chicago based artists that influenced your work?

Ted: To name a few I would include Vera Clement, Dan Ramirez, Barry Tinsley, John Bannon, and Mike Helbing. Gary Justice influenced me with works that on my best day I couldn’t even imagine, and still is doing it today. In sculpture I have always loved Richard Hunt’s work, Linda Lee’s, and yours.

Neil: On a more technical question, how do you start a painting—with drawing? And what materials do you work with—egg tempera, oil…? Also, do you have an image in your head, or do you find the image through the act of painting?

Ted: A new painting often comes from what I have just finished. Dreams are also the catalyst for new images. Most of the time, I have a hunch about where to go and then find it during the process. So, an initial application of an oil wash on a lead ground, becomes a drawing in charcoal or pastel, and then the serious paint application begins. If ever I have the entire painting decided at the beginning, it becomes something else anyway. Works on canvas or cradled panel have a lead ground and then are painted in oil.

Neil: How long do you work on a painting? The works seem a bit like a prize fight, as the record of everything that has happened seems contained within them. They have a certain raw explosiveness, as the unresolved tensions reach a détente, yet never a real ease of cathartic resolution. This seems very much a metaphor for who you are and brings me back to that restlessness and unease within the American dream.

Ted: Thanks, I completely agree. They usually take 3-6 months with some hanging around for years before I get them resolved. You have a good eye. I try to leave a map of how the work is produced by leaving an example of every layer and decision change. The closer I can get to the initial inspiration the more readily I can open the image to reflect the world I live in and perhaps leave a path for the viewer to find their world. That connection when it happens is powerful.

Neil: Likewise, how do you know when you are finished with a painting?

Ted: I know it’s finished when there is not a way to add another mark or color.

Neil: Some of your titles, reference a certain narrative, even though the later work is non-representational. Is there a lurking narrative behind the work, or is the work titled after completion?

Ted: Both, yes, as stated above, there is stuff lurking behind and driving every painting. Sometimes it leaks in at the beginning and gets a title, and other times, it comes much later, as I learn to understand the work. There will always be something to take me further or, for me, to find long after the painting is complete.

Neil: Your move from figuration to a more classical abstraction happened over several years. I remember some of the color field paintings, and their rich hues and almost translucent patinas. They were strikingly beautiful. How did you feel about that shift in relationship to the earlier work?

Ted: I feel that abstraction has been my mode since leaving high school. The figuration comes and goes but has always been a part of what I do, in fact the only painting I brought to Chicago from Montana is RODEO (1971), mentioned because it is a combination of both figuration and abstraction. So, think of me as mostly doing abstract works and now beginning to blend them with figuration. A visit on any given day will find both in progress. Again, I will mention that, for me, abstraction has always been more open to the viewer with many more points of access and opportunities for viewers to find themselves in the work.

Ted Stanuga (Left), Fractious, 2020. Oil on Canvas. (Right) Untitled, 2021. Oil on canvas, 54 x 48 inches. Photos courtesy of the artist.

Neil: You have had a long and productive Chicago career and have continued to paint while making a living. For me, that has been particularly impressive as you have worked through any number of adverse circumstances that would have challenged the rest of us. When were you able to focus entirely on painting?

Ted: Yes, as I chuckle, a great biography of me could be told by the jobs that I have been forced to have. Growing up poor and isolated, the first thing I had to do was get a job immediately and it has been month to month ever since. That should tell you much. The focus required for my work leaves me amid utter chaos in normal day to day activity. I don’t think that will ever change now.

Neil: As you have spent most of your life in Chicago, do you consider yourself a Chicago artist, or rather an artist who lives in Chicago? Is the work connected to the city visually?

Ted: I am an artist who lives and works in Chicago. I consider myself an American Artist.

Neil: What is your important accomplishment as an artist? In looking back, what were some of the high points of your career as an artist?

Ted: A recent high point was my show at Matthew Rachman Gallery, also curating the show of Veteran Art from the collection of the National Veterans Art Museum that traveled to St. Petersburg, Russia. The important accomplishment of my artistic life is to help veteran artists communicate what their experience meant to them and then to us.

Neil: You are experiencing some very difficult health related issues? How has that influenced your work? Is there a sense of urgency in the work?

Ted: Those things loom in the background—rage, as well as the paintings of the wrecked carousels. At the same time there is a need to bring color back to the conversation. Urgency, you bet, although I am fine with what is coming, I want to finish the chapter well.

Neil: Is there a closing statement for this essay, or something that I might have missed?

Ted: I am here and working because many people have contributed to my efforts through teaching, generosity, and by creating enough room around me so I was allowed work and think. Those who trusted me and gave me the chances I have had; I cannot thank enough.

Neil Goodman is a sculptor formerly based in Chicago with an extensive exhibition history. Presently living in the central coast of California, he retired from Indiana University Northwest as Professor Emeritus of Fine Arts. He is currently represented by Carl Hammer Gallery as well as serving as the South Central California Region Editor for the New Art Examiner.

Ted Stanuga. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Ted Stanuga, Untitled. 2017. Oil on Linen 76 x 80 inches. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Ted Stanuga (Left), Atlantic, 1991. Oil on Canvas, 120 x 72 inches.

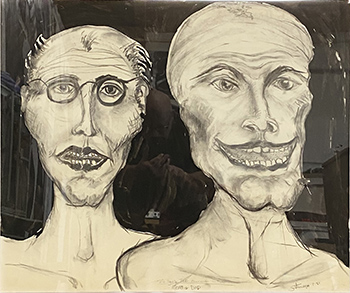

(Below) Mom and Dad, 1981. Charcoal on Paper. Photos courtesy

of the artist.

Ted Stanuga, Still Life with Urn, 1983. Oil on Canvas 64 x 64 inches. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Ted Stanuga, Consequence, 2008. Oil on Canvas 79 x 76 inches. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Ted Stanuga, Rodeo, 1971. Oil on Linen. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Ted Stanuga, Purple Heart, 1996. Oil on canvas. Photo courtesy of the artist.