Take My Picture at Wrightwood 659

by Rebecca Memoli

“Take My Picture” is the title of a photography exhibition at Wrightwood 659 and the prompt for how the photographs were created. Patric McCoy’s photographs provide an intimate view of Chicago’s Black gay community in the mid 80s. At a time of economic recession, the public perception of Black men was not favorable. The photographs on view, however, offer a different perspective of Black men than the stereotypes propagated in art and media. McCoy’s exhibition documents the lives of individuals, many of whom have been taken by the AIDS/HIV epidemic.

Coming from a line of photographers in his family, McCoy is self-taught. The project is not over conceptualized; it started as a written commitment McCoy made to himself, to take his camera everywhere and take a picture of anyone who asked. The trust these men have in the photographer is apparent. They are not set up nor are the subjects posed. They are not polished or pristine, but they are authentic. The moments McCoy has caught radiate through the dark shadows, or they have been arrested in the light of a flash.

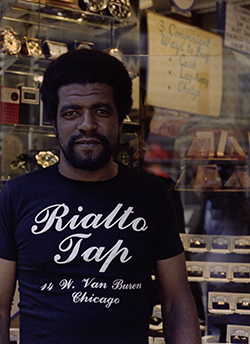

Wrightwood’s small second-floor north gallery is packed with portraits hung salon style like clusters of memories. Many of the images were shot at the Rialto Tap, a gay bar in the South Loop. The Rialto was a haven for those who were not welcome in the northside gay bars in Chicago. McCoy and his camera became a staple at the Rialto and along his bike route. He would make prints and give them away if he ever saw the person again. In an interview with Assistant Curator Ashley Janke, McCoy discusses the desire to have a good photograph, “I think every individual has a hunger to be depicted in a recognizable and positive light. People want to see themselves and be represented. That’s why we go to museums to look at images. They help us reflect on who we are.”

Art photography from the 80s tended to be from a white perspective. The most notable gay photographers of that time were white—for example, Vincent Cianni, Peter Hujar, Robert Maplethorpe, Duane Michaels, Harvey Milk, and Stanley Stellar. Photography of Black men in the 80’s, and certainly gay Black men, examine and often eroticize their bodies. Robert Mapplethorpe’s stunning studio portraits examine the Black body in terms of form, tone, and contrast, but they do not give the viewer a sense of who the men are as individuals. McCoy’s photographs portray gay Black men in a much more nuanced way. The subjects are strong, confident, but not guarded, which reflects a unique relationship between McCoy and the men he photographs. They have asked to have their picture taken, and this initiation creates a unique partnership between photographer and subject.

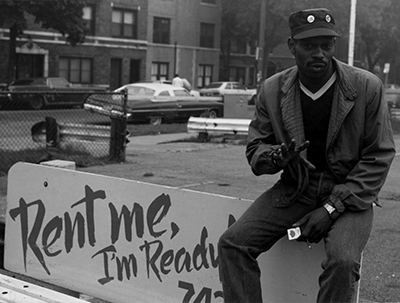

The men in McCoy’s photographs are portrayed as complex individuals rather than exotic or dangerous. They are not all “hustlers” like in Philip Lorca DiCorcia’s 90s project, although some may be. DiCorcia’s subjects are solicited in the same way, and for the same price—sex. He directs his hustlers to look moody and forlorn. Each scene is designed with cinematic lighting, the images read more like romantic era paintings than photographs of an underground community. McCoy’s men in contrast engage with the viewer in genuine and often playful ways. Like in the photograph Five,a man sits perched atop a bench that reads “Rent Me I’m Ready!” with his fingers open, indicating five… something.

Patric McCoy, Five, 1985. Digital archive print. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Patric McCoy, Five, 1985. Digital archive print. Photo courtesy of the artist.

McCoy’s approach to sexuality is far less sensationalized than that of DiCorcia and Mapplethorpe. The section called “The Look” contains photographs that subvert the power of gaze. The photographer is offered “the look” and thus the viewer is “transformed from spectator to prey” creating a completely shifted dynamic. In the photograph Window Look the subject gives the look directly into the lens, illuminated by soft window light. The intimacy conveyed in the look makes it stand out from the other more street style images.

Patric McCoy (left), Window Look, 1985. Digital archive print. (right) Z in a Box, 1985. Digital archive print. Photos courtesy of the artist.

McCoy’s photographs of the gay community are far less sexualized than works by other photographers at that time. By exhibiting these photographs now, Wrightwood 659 is following a positive trend of bringing attention and voice to black gay artists. What is most exciting is the historical implication of the work. In the 80s and 90s it is not that intimate photographs of Black gay men were not being taken, they were just not being shown. Just as Blacks were unwelcome in white gay bars, the interest and inclusion of gay artists was still primarily from a white perspective. Now the art world is looking back and finding what it has left behind.

Rebecca Memoli is a Chicago-based photographer and curator. She received her BFA from Pratt Institute and her MFA in Photography from Columbia College. Her work has been featured in several national and international group shows.

Editor's Note: Patric McCoy is a member of the Board of the New Art Association, the publisher of the New Art Examiner. The reviewer has never met Mr. McCoy and does not know him.

Patric McCoy, Rialto, 1985. Digital archive print. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Patric McCoy, Three Ways to Buy, 1985. Digital archive print. Photo courtesy of the artist.