Bruch Pepich, Executive Director, Racine Art Museum. Photo courtesy of Racine Art Museum.

Karen Johnson Boyd at the Racine Art Museum. Photo by Nicholsons’ of Racine.

Henni Keland in her home. Photo by Frank Paluch.

Frank Paluch at Perimeter Gallery. Photo by Crain’s Chicago Business.

Julie Lindermann and John Shimon, Trish and Matt Downtown (No. 2), Manitowoc, Wisconsin, 1995. Platinum palladium print, 9 7/8 x 7 7/8 inches. Photo: Racine Art Museum.

Brad Lynch. Photo by Nancy Keay.

Jan Hopkins, Isadora, 2008. Alaskan yellow cedar bark, grapefruit peel, lotus pod tops, Sharlyn melon peel, and waxed linen thread. Photo: Jon Bolton.

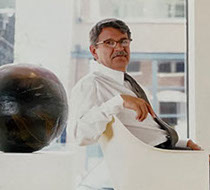

Jeffrey Lloyd Dever, Blossoming Radii, 2006. Polymer, nickel-plated, glass beads, and plastic-coated wire. Photo: Menina Meisels.

William Harper, Albino III (Brooch), 1978. 14-k gold, 24-k gold, enamel, pearl, sterling silver,quartz, and moonstone, 4 3/8 x 3 1/8 x ¾ inches. Photo: Jon Bolton.

Akio Takamori, Young Men with a Woman, 1992. Glazed porcelain. Photo: Jon Bolton.

Kéké Cribbs, Grainne Uaile, 1991. Glass and painted wood, 22 ¼ x 41 3/8 inches. Photo: Jon Bolton.

Kéké Cribbs, Grainne Uaile, 1991. Glass and painted wood, 22 ¼ x 41 3/8 inches. Photo: Jon Bolton.