No Words Spoken: The Ordinary in the Works of

Kyungwoo Chun

by Leandré D’Souza

Editor’s Note: Due to the length of this article, it will be published in the print version of the New Art Examiner in two parts. Part One will appear in the October 2023 issue and Part Two in the January 2024 issue. The entire essay is presented below.

PART ONE

Along the path to a Buddhist monastery lies a container filled with rocks of varying sizes. Next to it stands a table atop which rests a pile of red fabric. Pilgrims en route stop by. After a brief introduction with South Korean photographer and contemporary artist Kyungwoo Chun and his project team, each picks up a stone (or several of them) and places them inside a red fabric scrap. With a marker, the wrapped stones are labelled with their names and dates of birth. Intrigued by the long and patient queue, my three-year-old and I join in. We are told that each person is invited to pick the stone(s) that mirror the weight of the pain they carry. My son pulls the heaviest one out of the barrel, almost too large to lift single-handedly. Folded and tied securely into the square patch, we inscribe his details. The stone, now hidden, joins the others. 3,000 people pour their pain into these tiny parcels. Chun arranges the marked bundles in a grid on to the main temple square. Against a radiant sky, the stones’ burdens vanish beneath the ground that carries them.1

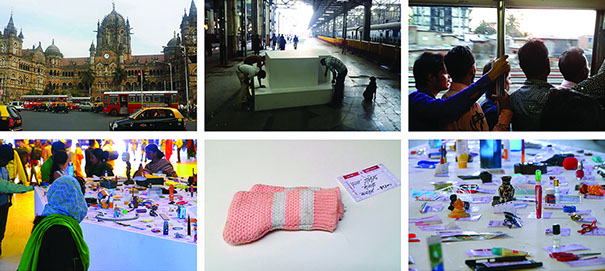

A table bench is constructed in the middle of CST Terminus that attracts over 3 million commuters daily. Happy Journey, 2015, public art project,[en]counters 2015—Spaces in Transition, ArtOxygen, CST Terminus, Mumbai. Photograph by Kyungwoo Chun, courtesy of the artist.

To relieve the heaviness of daily struggle, even for an instant, beckoned introspection and lingered with me. It also led to a decade long association with the artist. This resulted in a series of provocations in multiple contexts in India. Chun was recently in Goa, a state on the southwestern coast of India, where we launched his latest solo project at Sunaparanta Goa Centre for the Arts.2 Songs without Lyrics3 explores alternatives for lyrics with sounds that have no text. The works in the show make visible what is often not seen or as yet unknown, stretching our capacities for listening to sounds that are invented, and generating unimaginable possibilities for communication.

Mapping the Essence of Time

The human subject is a central motif in Chun’s practice. As a photographer, he is preoccupied with the superimposition of time that is inscribed into the image from an extended exposure. For the definition of photography, he draws from the 14th century Korean word Sa-Jin that was reserved for portraiture. The word meant depicting truth or soul, and therefore transcending the reproduction of the real. It is intended in this case, instead, as an “exchange of souls.”4 In Chun’s portraits, he constructs a studio setting in which sitters pose or perform a task for a prescribed duration—a few minutes, an hour, a full day. With the opening of the shutter, photographer and subject embark on a journey. A relational exchange evolves. What we see in the image is a hazy memory of the moments that were spent together. By enabling the experience of real time, consciousness awakens.

This process spreads beyond the photographic record and spills into video, performance, across several geographies, demographics, and social divisions. Fundamental to Chun’s research5 are the study of time as brittle, as caught between the present and what has just passed and is thus absent, and its asphyxiating bond with memory. He is concerned with how we interact in this world, how we relate to ourselves and others. Encouraging social cohesion, he creates situations inside which people (mostly strangers) enter into a framework conditioned by a set of instructions and actions. Like an alchemist, individuals are thrown together which provoke intimacies shown through physical connection. Inside the void, something shifts. The ontological experience moves from the sight to the touch. The body loosens, is freed into a state of sheer abandon and opens itself to new imaginations.6 Sensations of love and compassion flourish. The human soul starts to flutter.

With utmost perfection, Chun intuitively pieces the ingredients together and steps back, allowing time, space (void), and the vibrations that simmer between them to simultaneously morph. In the interim between creation and dissolution, surfaces dissolve. These transient encounters are repeated, over and over, till they arrive at the ritualistic. Chun is testing the nature of being and existence. Within this deeper philosophical inquiry, participants probe the meaning and experience of time. Through the impulse of emotion, a new language arises. The subjects, in their union, are no longer in isolation but are joined together. The residues of these experiments form a landscape, mapping human interactions and the memory of existence.

Activated through the dialectic between the absence of what has passed and presence, a tension is triggered.7 A reserve of memories flows into the empty vessel, stimulated by the interdependence of beings. Each present moment crumbles into the recesses of memory. But rather than widen the distance between the self that is now unfamiliar and what exists in real time, the interconnectedness grows closer. Andrey Tarkovsky states “Time cannot vanish without trace for it is a subjective, spiritual category, and the time we have lived settles in our soul as an experience placed within time.”8 Thus, as the psyche transitions, enabling the exposure of the inner self, experience turns limitless.

As witnesses and participants in these investigations into non-linear processes of memory and time, we begin to understand that the core of Chun’s process is to push us into a state of nothingness. Through embodied experience, through our fundamental connection with others, we chance upon acts of care. It is in our very essence. We are instinctively predisposed to forming meaningful relations where we can share love, sorrow towards or with others. It is reciprocal and can only be imagined as a collective act.

Care also treads between devotion and burden. Throughout these ephemeral and constructed settings, people unknown to each other, enter into a state of mutual dependence. With bodies heavy against each other, they determine the level of comfort or dis-ease that will transpire. As Chun remarks, “We’re strangers only for as long as we feel estranged. Even if it’s someone you’ve only just met, you may feel comfortable together or you may remain strangers—although remaining strangers is something that makes us anxious.”9

Chun pushes the boundaries of authorship, maintaining a distance, but his presence is still imprinted and perceived. Chun dissipates hierarchies and separation between artist and participants, as well as between the subjects with cutting-edge work in the relational.

Travellers at the station are asked to share with the artist an object that belongs to them. Happy Journey, 2015, public art project, [en]counters 2015 – Spaces in Transition, ArtOxygen, CST Terminus, Mumbai. Photograph by Kyungwoo Chun, courtesy of the artist.

Travellers at the station are asked to share with the artist an object that belongs to them. Happy Journey, 2015, public art project, [en]counters 2015 – Spaces in Transition, ArtOxygen, CST Terminus, Mumbai. Photograph by Kyungwoo Chun, courtesy of the artist.

The intent is not to represent individual identities (selves), but to make visible the “existence of a phenomenon.”10 This is manifested in the concentration on the basics. The exterior is stripped bare and what remains in the photograph/video/performance is the movement of time—what occurred between Chun and the person(s) involved and the conversations that evolved, even if not one word was said.

The works, in amorphous states, give a sense of something that happened, a sort of incompleteness—time capsules where its rhythms are expanded and slowed down.11

The Emotional Value in the Relational

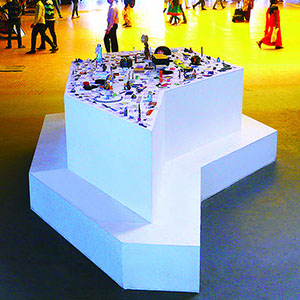

In early 2015, Chun interceded in Mumbai’s Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus (CST),12 its main railway station, in a project called Happy Journey.13 The terminus site is particularly hectic, busy, and challenging for an artistic intervention. It receives more than one million commuters daily, always in a hurry, rushing off trains on their way to work or to catch their return journey home. Chun resolved to tackle this hindrance by placing a white table-bench sculpted in the form of CST at one of the stations’ platforms. People were invited to rest while waiting for their trains. During this stretched time, he would invite commuters to share with him personal objects: a rabbit’s foot for good karma, a child’s toy chewed by his dog, an x-ray, a precious bangle from birth. Anything personal. He only posed one challenge: commuters had to think about his request, go where they were headed and then return with the selected object. The artist wanted the people he met to invest some time and consciously decide to be a part of the project. By sharing a piece of themselves with the artist, they were intentionally giving a part of their lives to the work. Without them, the blank surface and shape of the sculpture would not have had any meaning. Each object shared was marked with the name of the person who gave it, the place from where it originated, and the distance it had travelled to arrive at the site. The tagged object was then placed on the sculpture. What emerged was a silent, objectual archive of stories of workers and commuters, city-dwellers who are not part of the city’s dominant discourse, but very much part of its economic backbone.

Time becomes an important factor in the work; it is the occasion which allows the encounter to happen, and in its duration, relationships are established. Chun asked rushing commuters what was lacking in their lives. It was time. By being present at the site, speaking to people, listening to stories of hopes, dreams, failures, wishes, and the interrelations that emerged out of the work, both Chun and the ‘participants’ were left with a bond. In some cases, this turned into participation. In other instances, they were both left with the memory of their encounter. The artist played on notions of space, time, and memory as he subtly persuaded the participants into thinking about the encounter, the absurdity of his request and the significance of their mindful involvement. In this case, value was found in the ordinary object, in the memory it was connected to, and in the relational experience which generated it.14

Part Two

Silence as a “Being Together” of Existence

Ordinary Unknown15 is a durational piece that marked the artist’s first production in Goa. An open call was launched where locals could register to a performative meal. A total of 30 responded and were subsequently called to dinner with specific guidelines.

As the visitors arrive, they are asked to sit together just like they would with friends and family at a dinner. Only here, the conditions are altered. The guests are seated at a table set with 15 meals containing Goan delicacies. Divided into two groups, row A is instructed to feed the person before them in complete silence for 10 minutes. This is followed by row B who repeat the same action towards their fellow partners.

The act of feeding is symbolic. It is a sign of nurturing and sustenance. We recall that as children, our mothers and grandmothers would feed us. Our earliest memories of love are associated with food. Here, Chun reverses the action where participants are not fed according to their normal routine. Instead, they taste and experience ways of eating of the person(s) in front of them. What does the combination of flavors or choice of accompaniments reveal about this unknown individual? And what does it tell the participants about themselves? As control is lost, anxiousness dissipates and trust seeps in.

Over 20 minutes, some use their hands and form little morsels of rice and vegetable softened with a dip into curry to moisten the palate. Another gently wipes the mouth of his partner. Others begin with dessert and then move on to the meal. Some prefer the meats and leave out the vegetables. Others avoid the spicy offerings and opt for the blander items. A participant recalls his mother and is moved to tears.

As Chun explains, “eating is one of the most basic human needs. It is essential to our survival. But we forget that there is a difference between food and tasting, biting, chewing. The food that one chooses and consumes penetrates our body and becomes a part of us. Thus, eating is a dialogue with oneself.”

In silence, an attachment starts to form. Vulnerabilities shed and the harsh and distant exterior that the guests arrived with begin to soften. There is a closeness that emerges, a “being together of existences,” says Chun.

Suspending Perfection in Favour of Failure

The situation that evokes our human frailties is further elaborated in Dabbawala’s Lunch.16 In 2017, Chun wanted to work with the dabbawalas of Mumbai. They are a metal lunchbox delivery and return service providing hot meals to city workers. It constitutes a system that dates back to 1890. Meals are prepared in customers’ homes that are picked up, delivered to people at work, and the empty tiffin boxes returned the same day. The metropolis has 5,000 dabbawalas transporting 130,000 meals daily. This network in Mumbai is the city’s most efficient manually run delivery systems.

Chun wanted to inquire into the human aspect of their work. Nobody ever thought to provide the dabbawalas with a hot lunch or make them feel just like the clients they serve. Working from a distance, Chun mobilized the curatorial and production unit that was part of this project and directed us to contact the association representing the dabbawalas. The union heads were excited to teach us about their network and functioning. We were given a glimpse into the coding structure that was followed district-wide and the regimen that the workers had to follow in order to ensure the smooth administration of consignments. They amount to 260,000 transactions in six hours each day, six days a week, 52 weeks a year. During lunch hour, we met with 50 dabbawalas and asked them to share with us their wish meals. Placing their order, the dabbawalas’ 50 wishes were listed along with their addresses, 50 steel boxes were handed over and coded with their names in red ink. Our task was to cook, pack, hand deliver the lunches as surprises to the homes of the participants.

The 50 lunch boxes coded with names of each dabbawala along with their addresses for delivery. Dabbawalas Lunch, 2017, [en]counters 2017 – Daily Ration, ArtOxygen, Mumbai. Photograph by Kyungwoo Chun, courtesy the artist.

However, any attempt at replicating their lives was bound to backfire. Using modern ways of demarcating addresses, meals and consignment schedules instantly backfired. What began as a simple gesture to provide a meal, turned into a complex negotiation and strategising between the dabbawalas and the team on how to adapt newer (more grassroots) methods to ensure effective deliveries.

The focus of the work shifted from the meal to the alliance that was being established between the new ‘performance’ deliverers and the dabbawalas. Roles that were well-defined at first began to entangle. It was no longer clear who was the carrier and who was the receiver. Swapping roles meant that we needed to invent our own methods to be able to devise a plan where lunches could be delivered to the 50 dabbawalas before they left their homes, studying with great care their travel schedules and routes. Meals were prepared the night before delivery. They were heated at dawn and packed in steel containers. A travel route was mapped commencing with the furthest destination and leading up to the home closest to the city center. Timing was everything. One delay meant that the dabbawalas would leave their homes with no food.

But our interventions disturbed their daily actions, making any kind of precision impossible to reach. This sense of bewilderment, where faults are allowed to occur, suspends the human need for perfection and success, restoring instead the importance in the values of trust, sharing, belonging, acceptance, tolerance, and failure.

Acts of Listening

Chun’s pursuit to find the “intangible in humans”17 is examined in a series of collaborations with a local children’s choir18 in Goa on the occasion of his solo exhibition Song Without Lyrics19 that opened in August 2023. In an effort to uncover new modes of transmitting and receiving messages, Resonance is a photographic performance in which children are asked to sing to trees. A resonance refers to the synchronous relationship between two objects, where the vibrations released in one body are caused by sounds produced by the other. Over multiple evenings, Chun places each child within a canopy of trees. In the midst of dense foliage and cuddled in nature’s embrace, the children serenade the trees. Frequencies start to warp between the plants and the children as leaves flutter ever so slightly, soothed by the pulse of their voices. This gesture, repeated over days, is recorded in one shot timed by the duration of each song. The singular frames capture the overlapping of motion, notes, and synergies between each child and tree. Each portrait undergoes a process of solarization, so that the hues appear suffused with a soft lightening. Confusing the distinction between man and nature, what is discerned from the final impressions is the memory of this momentary dialogue and the communion between the two living elements.

The Ektaal Children’s Choir perform in a constructed situation, activating the picture scores composed by Koreans with hearing and speaking disabilities. Songs Without Lyrics II, single channel video, 2023, Songs Without Lyrics, Sunaparanta Goa Centre for the Arts. Photograph by Kyungwoo Chun, courtesy the artist.

Chun’s association with the choir continues in Songs without Lyrics II. The members are invited to select a series of pictograms composed by Koreans with speaking and hearing disabilities.20 Representing one of the composers, each child creates their own melody and sings for the original composers of the scores. Gathered together, they are placed in a situational video performance. Positioned in two rows, they are given random numbers correlating to the order of each performance. They must sing individually at first. Filmed in black and white, time appears to have ceased altogether. Against this sense of timelessness, the voice is soft with a quivering apprehension. It then gains momentum. And stops. Another takes over. As the voices enter and leave the frame, the choir listens to each other. There is a tension that grows as the camera pans up close to an eye, ear, or mouth. We can feel the nervousness in some, boredom in others. One bites his lips, another twitches her nose, someone else counts the notes on his fingers. Once the individual scores are finished, the choir sing together in discordant unison, some chords clashing, others harmonizing.

Close-ups of children as they listen to their peers and wait their turn to sing. Songs Without Lyrics II, single channel video, 2023, Songs Without Lyrics, Sunaparanta Goa Centre for the Arts. Photograph by Kyungwoo Chun, courtesy the artist.

In Search of Love

How do we measure life? Are we judged by our quest for the ideal? At the root of the human condition lies a relentless and restless search for love. Chun’s practice orients itself around the most unlikely subjects. The temporal settings and the conditions that are formulated become the witnesses for something to take place between people who are brought together. It all begins with the body. With a subtle altering of daily life, he guides us into unfamiliar territory where the enactment of ordinary tasks thrusts us into a vortex. We confront our own nature and what this implies. Chun thus becomes the conduit, and the meeting is the catalyst that brings to light what was embedded deep in our consciousness but, until now, lacked form.

Our external selves are left at the fringes. In our endeavour to locate the path, we are either repelled by the meeting or embrace it. With Happy Journey, the mediation of the artist with various commuters at the station either results in rejection or empathy, but, in the time made available, the encounter finds a sufficient source of value. The action of eating, vital for human sustenance, is challenged in Ordinary Unknown where an emphasis is placed on the tender co-dependence of beings. Testing our tolerance for defeat, the delivery of the wish meals to the tiffin wallahs as part of Dabbawala’s Lunch ends in confusion and utter chaos. In Resonance and Songs Without Lyrics II, as humans converse in nature and with each other, they learn to perceive and listen to themselves.

Once we cross over the threshold, time fragments. A sense of flux takes over. Time speeds up and then slows down. The heart is perplexed, unsure how to tread. Our sense of control slackens, and we surrender to the moment. It is amidst this disorder, that we are confronted with divergent trajectories. Do we gravitate towards the mirror self, or do we shove beyond, reclaiming love that can enable us to live and grow with others? Do light and shadow separate, or do they dissolve into union with one another? Do we commit to compassion and empathy at the individual and collective level?

We return to our inherent, spiritual selves. And within this single bubble emerges a multiplicity of experiences, sensations, and states of being. The creative function does not transmit a sense of redemption. Instead, it leads us to a love that is not utopian. We meet, touch, feel, and share it. In this sacred space, the act of love is subversive, and social bonds can be restored.

It is in this in-between liminal space where relationships can emerge, communication takes place, and vulnerabilities can breathe. For the artist, seeing and listening are the same. We don’t only see with our eyes or listen with words. Our inner voice begins to speak. Body, image, and speech are wrapped in the dynamism of love. In silence and with no words spoken, time passes by.

Leandré is the curator and creative director at Sunaparanta Goa Centre for the Arts. In 2023, she was invited as mentor to the two-year South Asia Incubator Programme at PhotoKTM (Kathmandu, Nepal). Leandré is the founder of ArtOxygen, a collective aimed at curating and producing art projects in open spaces. From 2010–2018, she organized [en]counters, a festival dealing with issues affecting the everyday life of Mumbai. She was invited to curate the participation of Indian and international artists at the biennial Haein Art Project in South Korea in 2013 and curated the 2015/16 & 2018 editions of Sensorium at Sunaparanta Goa Centre for the Arts. In 2014, she received an award for Culture and Change from the Prince Claus Fund for Culture and Development.

Footnotes

1. The Weight of Pain was realized as part of the second edition of the Haein Art Project, a biennial public art project held in 2013 in South Korea. Initiated by a group of Buddhist monks from the Haeinsa Temple, a UNESCO world heritage site and repository of the Tripitaka Koreana, the most complete collection of Buddhist texts worldwide, the project aimed to investigate the connections between contemporary art and Buddhism.

More than 30 contemporary artists from across the world were invited to explore the theme of MAUM, which in Korean refers to exploring the idea of the heart and mind. The participating artists created site-specific projects as they interpreted the theme and its various declinations that allude to healing, communication, energies, relations, and interactions between people. http://www.kyungwoochun.de/data/public/public.php?id=public-05.

2. Sunaparanta Goa Centre for the Arts is a not-for-profit initiative founded by Dipti and Dattaraj V. Salgaocar. Since its inception in 2009, its vision has been to preserve Goa’s creative legacy, to encourage cultural growth in India, and to promote a range of cultural activities across various media, geographies, and time frames. Over the years, the Foundation has worked towards cultivating a program that brings together a plurality of voices and practitioners from various creative disciplines.

With the patronage of Isheta Salgaocar, the Foundation has evolved into a bridge connecting Goa to India and the world, enabling the addressing of questions concerning the contemporary social and cultural environment, reflected across the spectrum of its work.

Today, exhibition formats have expanded and are directed towards generating a laboratory of ideas that address questions concerning sustainability, redistribution of resources, and ecology with greater urgency.

The Foundation’s pedagogical programmes include the Sunaparanta Art Initiator Lab (a mentorship programme that is practice-based, open to creative professionals from various streams and offers them the opportunity to refine their practices through innovative learning (and un-learning) methodologies); the Artist-in-Residence Lab (research-based and offers a space for artists/curators/writers/researchers to critically examine existing practices through exchange and dialogue); Fellowship Grants (for cultural operators producing scholarly work in various creative fields); Emerging Artist Grants (contributes to the advancement of research, practice and production); Art & Theatre School (places children at the forefront of learning and thinking where they become the protagonists in open and process-based art and theatre practices). www.sgcfa.org.

3. Songs Without Lyrics marked the first solo show of Kyungwoo Chun in Goa, India. It began with a series of collaborations with the Ektaal Children’s Choir, and it also presented in-situ, photographic, video, and performance works. https://sgcfa.org/Kyungwoo_Chun_Brochure_2023.pdf.

4. Kyungwoo Chun reveals: “I believe that photographing people always involves an exchange of souls up to a point and that this exchange is singular and unique to each photograph. You sense the energy inherent in both space and time and create an image that is both.” Susanne Pfeffer, “Sometimes we forget we’re alive …,” Interview with Kyungwoo Chun, Hatje Cantz, 2005, http://www.kyungwoochun.com/texts-pdf/susanne-pfeffer.pdf.

5. Lori Wike, “Photographs and Signatures: Absence, Presence, and Temporality in Barthes and Derrida,” in InVisible Culture: An Electronic Journal for Visual Culture, Issue 3, 2000, p 1-9, https://www.rochester.edu/in_visible_culture/issue3/IVC_iss3_Wike.pdf.

6. “Western’s love tradition has mostly located love as an experience connected to sight, and as such as somewhat unattainable. However here love is ‘allowed’ and as such enables us to touch things. It is an ontological experience that moves from the eye (‘you’ll see the sun’) to a meeting enabled by touch. Seeing become touching, and humanity is accordingly freed: ‘you are allowed to love’,” Yoav Ronel, “‘Exiled From All Gregarity’: Profane Love, Poetics and Political Imagination In Barthes and Agamben’,” in TheoryNOW Journal of Literature, Critique, and Thought, p 3, https://www. academia.edu/38324007/_Exiled_From_All_Gregarity_Profane_Love_Poetics_and_Political_Imagination_in_Barthes_ and_Agamben.

7. While, as mentioned earlier, intentionality in this sense is not an issue that Barthes takes up, the presence of the referent is an important subject for both writers. In fact, one could easily substitute “photograph” for “signature” in the following passage from Derrida: “By definition, a written signature [photograph] implies the actual or empirical non-presence of the signer. But, it will be claimed, the signature also marks and retains his having-been present in a past now or present [maintenant] which will remain a future now or present [maintenant], thus in a general maintenant, in the transcendental form of presentness [maintenance].... In order for the tethering to the source to occur, what must be retained is the absolute singularity of a signature event [photographic-event] and a signature-form [photographic-form]: the pure reproducibility of a pure event.” Lori Wike, Photographs and Signatures: Absence, Presence, and Temporality in Barthes and Derrida, ibid, p 4-5.

8. “Time can vanish without trace in our material world for it is a subjective, spiritual category. The time we have lived settles in our soul as an experience placed within time.” Andrey Tarkovsky, Sculpting in Time: Reflections on the Cinema, translated by Kitty Hunter-Blair, University of Texas Press, 1987, p 58, https://monoskop.org/images/d/dd/Tarkovsky_Andrey_Sculpting_in_Time_Reflections_on_the_Cinema.pdf.

9. Elucidating on the relational element that emerges through situational performance, Chun comments: “We’re strangers only for as long as we feel estranged. Even if it’s someone you’ve only just met, you may feel comfortable together or you may remain strangers–although remaining strangers is something that makes us anxious.” Susanne Pfeffer, Sometimes we forget we’re alive …, Interview with Kyungwoo Chun, ibid.

10. When asked about the phrase, “I photograph not what I see, but what I believe exists,” Chun replies, “I’m much less interested in the search for motifs, or rather in my visual environment, than I am in the idea of what would be possible. Making the existence of a phenomenon visible may be laborious, but it’s always worthwhile. Of course, photography has to do with direct reality, yet it also has to do with the belief that there are many different ways of viewing the same thing. Believing really is seeing.” Susanne Pfeffer, Sometimes we forget we’re alive …, Interview with Kyungwoo Chun, ibid.

11 “Chun … makes time portraits: portraits of time using slow, minute-long exposures of people. The portrait becomes a kind of vera icon—not of the person, but of lasting time, of appearance; not of individuality, but of the state of being human, of existence in general: typified intuitive space versus linguistic, formalized identification.” Urs Stahel, Travelling Faces, Circulating History, Kyungwoo Chun-Thousands, Hatje Cantz, 2008.

12. The Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus, formerly known as Victoria Terminus Station, is a UNESCO World Heritage site in Mumbai that serves over 3 million passengers daily.

13. Founded in 2009, ArtOxygen (ArtO2) is a Mumbai-based art initiative curating and producing art projects in urban spaces. From 2010-2018, it organized [en]counters, a yearly art project in public spaces exploring issues related to Mumbai's urban landscape and encouraging creative ideas & actions that transform the city's everyday life. Spaces in Transition, 2015, was the 5th edition of the project that focused on the action of moving and commuting in Mumbai’s transportation network. A total of twelve projects were realized by Indian and international practitioners. Each prompted a reaction to the following questions: how is Mumbai’s landscape perceived by commuters; How can trains, buses, cabs and rickshaws be turned into places for temporary sociability; and how can the suspended period between departure and destination become an occasion to critically re-think urban and public spaces?

The aim of the project was to promote the use of public transportation by making commuting/moving in the city a more enjoyable activity—generate a sense of civic pride, belonging and of ownership; to trigger collective imagination and critical thinking; and to provide wider accessibility to contemporary arts by using urban transportation networks as a shared platform.

Spaces in Transition was realized with the support of the Prince Claus Fund, under the award for Cultures for Change. https://youtu.be/xdO23myGpn0?si=Khkz0WuRCZ7j6ZBA.

14. In this approach, the life of the work is contingent to the will of the subject, who is no longer just a spectator, but a partner, as s/he determines how s/he wishes to be represented. This confuses the stratification of each person having a pre-defined task and specific way of doing or seeing. And the only way this disturbance can be recurrent, and to determine whether equality is indeed possible is through repeated experimentation. This also gives way to new kinds of knowledge production, based on the intellectual capacity of each individual that is unleashed when encountering and engaging with the artistic process. “Aesthetic experience eludes the sensible distribution of roles and competences which structures the hierarchical order”, Jacques Rancière, Thinking Between Disciplines: An Aesthetics of Knowledge, Jon Roffe, trans, Parrhesia,1, 2006, p 4.

15. Ordinary Unknown was realized as part of the Sensorium 2014/15 Festival at Sunaparanta Goa Centre for the Arts, https://sgcfa.org/SENSORIUM_2014-15_CATALOGUE.pdf

16. Daily Ration was the 8th edition of ArtOxygen’s annual public art project that invited an examination into Mumbai's diverse & heterogeneous food culture. Artistic interventions from India and abroad celebrated this unique characteristic of the city, returning attention to the value to “food,” one of the most vital elements of our daily lives, https://youtu.be/BZUn9mEkIbo?si=GFLToLD_jP_mp97K

17. Jiyoon Lee writes in reference to Kyungwoo’s perspective on photography as not just a medium but also a responsibility to find the “intangible in humans.” Jiyoon Lee, Resonance of Time, Space and Self, Kyungwoo Chun – Performance Catalogue Raisonné I, IANN Books, 2011, http://www.kyungwoochun.de/texts-pdf/JLee.pdf

18. Ektaal Children’s Choir was formed in 2014, under the guidance of Nayantara de Lima Leitão (vocal coach/conductor) with an aim to introduce children to choral music, harmony and meaningful interaction.

19. Songs Without Lyrics, ibid.

20. In 2021, the artist worked with 16 Koreans with speaking and hearing disabilities who were invited to compose a musical piece that they wished to sing to others. They were asked to provide a title and to draw a picture score with colors, pictograms and numbers corresponding to the melody and length of tone. In Korea, the sound sequences were spontaneously activated by sounds of bells. Seosomun Shrine History Museum, Seoul.

Recordings of children in dialogue with nature. Resonance, 2023, Songs Without Lyrics, Sunaparanta Goa Centre for the Arts. Photograph by Kyungwoo Chun, courtesy of the artist.

The CST Terminus transforms into a repository of objects and a peoples’ archive. Happy Journey, 2015, public art project, [en]counters 2015 – Spaces in Transition, ArtOxygen, CST Terminus, Mumbai. Photograph by Kyungwoo Chun, courtesy of the artist.

A group of strangers feed each other and form an indelible bond with their partners and themselves. Ordinary Unknown, 2015, performance, Sensorium 2014/15, Sunaparanta Goa Center for the Arts. Photograph by Kyungwoo Chun, courtesy the artist.

Dabbawalas gathering at the union as they share their wish lunches with the artist. Dabbawalas Lunch, 2017, [en]counters 2017 – Daily Ration, ArtOxygen, Mumbai. Photograph by Kyungwoo Chun, courtesy the artist.