Celestial Stage

Michiko Itatani at Wrightwood 659

by Annette LePique

There’s a certain ambivalence inherent to an encounter with Michiko Itatani’s work. In each of the 65 paintings and drawings that compose Wrightwood 659’s “Celestial Stage,” the artist’s optimism in human discovery exerts a compelling force upon the viewer. Itatani believes in the promise of human inquisitiveness in the face of an unmoving universe. Such faith breeds wonder: it is the feeling that every discovery, from the printing press to the Hadron Collider, brings forth something good. There is an implicit trust in the possibility of human progress. Yet, under the market’s invisible hand, Itatani’s faith proves difficult terrain to navigate. Who can be free to wonder under mass inequality? What can discovery look like when the planet burns? What can optimism feel like when it is sold to the highest bidder?

Such questions spiral into larger ones. Who is left behind under progress built upon the backs of others? How can we come together to wonder, to create, to move forward, together?

This is the bind you find yourself in when experiencing Itatani’s scenes. While viewers can chart the changes in the artist’s practice through “Celestial’s” shifts in visual vocabularies, they can’t ignore the artist’s consistent fascination with humanity’s search for knowledge. Recalling the memory palaces of antiquity, Itatani creates architectures of the mind to explore how and why humanity desires to understand the world. For Itatani, knowledge ties intimately to the arts and technology, pursuits that express humanity’s vulnerabilities and resilience; the shared desire to connect with one another, to know and be known.

From monumental geometric forms to dynamic interior scenes, Itatani’s images suggest interrelation and the dynamic potential of art or technology in all Itatani’s pieces. Yet even with all of her rockets, trombones, globes, pianos, telescopes, and harps, Itatani is a painter conscientious of scale. Both scientific and musical instruments are miniscule against windows that reveal vast expanses of the cosmos. We, the viewer, also remain small against these starry skies. Each piece functions as a stage for these slivers of human potential against the immensity of the university, a moment in a long line of moments. This is the human condition: an inescapable, unavoidable ephemerality in the face of a burning desire for permanence, for solid ground beneath one’s feet. Yet the world keeps turning unabated, and the land beneath crumbles away. Here lies the work Itatani asks of viewers. How do you—how can you—believe as the world burns? Where does beauty live in a world like ours?

Itatani is a storyteller: As a young adult, she aspired to become a fiction writer. Her early short stories are reminiscent of William Gibson’s cyberpunk noirs and Octavia Butler’s speculative futures. One such story, titled “Encounter Seven” and included in the show’s catalog, speaks to the interests that haunt her body of work: what it means to be alone, to know, to doubt, to believe in another, to have faith. The idea of faith is Itatani’s central concern: faith in humanity, faith in the future, faith in a future.

Untitled painting/installation 78-J-3 (1978), the oldest of the works on view, is a monolithic column created from canvas and acrylics. Eighty-five inches tall, the piece is painted a deep matte onyx with rivulets of metallic silver undulating over the surface. Itatani utilized a syringe to form the metallic lines that skim across the work’s velvety black backdrop. In the exhibition’s catalog, these lines are compared to a fine mesh or the delicate staff lines within musical notation, an observation befitting Itatani’s reverence for the arts. Yet these slopes and whorls also share kinship with lines of planetary orbit—that is, paths of transformation and movement. The monolithic structure speaks to the mysteries of faith: think Stonehenge and humanity’s predilections to memorialize, with the inky canvas embodying a compact unknown.

Let us think of Untitled as a guidepost for Itatani’s practice and its many iterations. “Celestial” showcases distinct stages within Itatani’s oeuvre that can be identified through the artist’s experiments with scale, color, space, and line. In Itatani’s Tesseract Study 21-F-1 through F-6 (2021), precise graphite lines dominate the compact frames. Each of the works in the series depicts orbital lines bursting forth from a central polyhedron figure, the titular tesseract. Though it is left to the viewer to identify whether the lines are the paths of atomic or planetary material, the scale of each piece (measuring no larger than a foot squared) leads the viewer to assume the renderings are at the level of atomic particles. Such experimentation with size and perspective is intriguing when we think in terms of intimacy, connection, and presence, for what is humanity’s desire to connect, to know, if not a desire to be known in return? The search for knowledge is a confirmation of one’s presence in a vast and sometimes overwhelming world. The act of leaning forward to grasp the intricacies of each piece forces the viewer to engage the work in a new way, a movement which serves to rearticulate the questions of permanence that run throughout the exhibition.

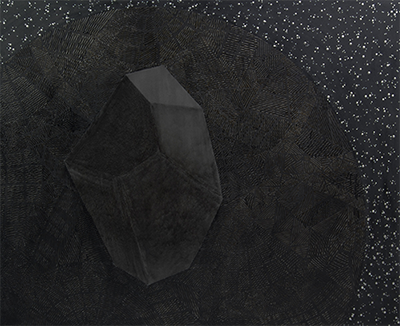

The figure of the tesseract reappears throughout Itatani’s work. In Cosmic Encounter 19-D-7 and D-8 (2019), pinpricks of light, luminous oils haloed in shades of blue surround the central figure, darkened in shades of black that deepen in opacity and tone. Itatani’s tesseract has been likened to the figure in Albrecht Dürer’s Melancholia I (1514) and Alberto Giacometti’s Le cube (1934), both pieces that take the process of creating art and human genius as their central ground. While Itatani’s engagement with the tesseract also touches upon the struggle and desire inherent to artistic creation, there is also an element of ritual within the figure’s repetition. The tesseract here is indicative of the decision to consciously pursue art, pursue knowledge, and pursue connection in the face of the ephemeral. The figure is the tension, the friction inherent to the human condition: the finality of death.

Death and its many questions loom throughout the exhibition, for what gives art meaning if not that it asserts all of life’s brilliant viscera? There is a certain comfort to be found in these unavoidable ends; Itatani, I think, finds pleasure in these shadowed spaces too.

In Itatani’s painted halls, there is a recognition of humanity’s foibles and weaknesses, of our smallness and persistence within the chaos, of our ceaseless searching. These central stages, some painted with vibrant colors and others that shimmer in cool grays, are the exhibition’s exposed nerves; they gush with electricity. They are ambivalent and ambiguous, constantly questioning with no clear answers in sight. This speculation is the bedrock of Itatani’s belief in humanity: it is doubt that imbues our need to connect, however briefly, with meaning.

It is this search that stands at the heart of Itatani’s practice; it is the choice to believe in one another, the choice to make, the choice to create. Choice is the first step: we must choose to believe in one another and build something better, together.

Annette LePique is an arts writer. Her interests include the moving image and psychoanalysis. She has written for Newcity, ArtReview, Chicago Reader, Stillpoint Magazine, Spectator Film Journal, and others.

"Personal Codes" from Cosmic Geometry 19-B-4, 2019. Oil on canvas, 78 x 96 inches. Photo courtesy of Michiko Itatani.

"Distant Earth & Moon" from Infinite Hope 22-C-2, 2022. Oil on canvas,

48 x 60 inches. Photo courtesy of Michiko Itatani.

%202011%2078x96%20oil%20on%20canvas%20mi.png?crc=452841863)

"Cosmic Wanderlust" from CTRL-Home/Echo 11-B-1 (CHR-2), 2011. Oil on canvas, 78 x 96 inches. Photo courtesy of Michiko Itatani.

%202011%2096x78%20oil%20on%20canvas%20mi.png?crc=4001072788)

"Cosmic Wanderlust" from Cosmic Theater 11-B-2(CWC-6), 2011. Oil on canvas, 96x78 inches. Photo courtesy of Michiko Itatani.

Albrecht Durer, Melancholia I, 1514. Engraving, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Alberto Giacometti, Le cube, 1934-35. Bronze,36.8 x 23 x 22.8 inches. Photo: Foundation Maeght.