Hangama Amiri: A Homage to Home

The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum

by Dominick Lombardi

In 1996, when Hangama Amiri was seven years old, her family fled Kabul, Afghanistan. That was the same year that the Taliban established an Islamic State, assassinated the then president Mohammad Najibullah, and established uncompromisingly harsh laws limiting rights and freedoms, especially for women. What the influence and ideals of the Taliban could not control was the memories of those who escaped to foreign lands, those who carried with them the creative and colorful culture of their lost land, and the spirit and soul of its people.

Hangama Amiri, A Homage to Home (installation views), The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum. Courtesy of the artist and COOPER COLE, Toronto, and T293, Rome. Photos: Jason Mandella.

Those precious memories of the young Hangama Amiri, especially the hustle, bustle, and chaotic beauty of the outdoor markets and bazaars, comes into full view in her current installation at the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum. The exhibition is titled “A Homage to Home.” Consisting of a number of flowing fabric assemblages, banners, objects and studies, “A Homage to Home” speaks very specifically to Amiri’s more distinct memories encountered as a hopeful Afghan child. In addition to her distinctive visual experiences, Amiri speaks to us through her art, about her mother’s guidance when it came to mastering sewing. Her memories of her uncle’s related profession as a tailor completes the picture.

The fabrics she chooses for this installation have very clear references to the type she remembers seeing as a child at street bazaars. They range greatly in sheen, texture, color, and pattern, making for a most compelling and enlightening visual experience for visitors of this exhibition. Working with the Museum’s Chief Curator Amy Smith-Stewart, Amari pushes her desire to present a clear presentation of the past, going as far as adding an absurd, drooping, black, electrical wire along the ceiling of the museum to suggest the haphazard way in which the bazaars quickly come together with little concern for regulations. The one element in the exhibition that looks awkward or out of place is the lone neon based plexiglass monolith Nakhoonak-e Aroos/Bride’s Nail (2022). Compared to the rest of the installation in this main room, Nakhoonak-e Aroos/Bride’s Nail is too austere, visually harsh, and abrupt. It could have made sense in a small, darkened room off the main gallery, or left in place and softened a bit by placing it within a fabric setting. The way it is here only serves as an abrupt distraction.

The fabrics she chooses for this installation have very clear references to the type she remembers seeing as a child at street bazaars. They range greatly in sheen, texture, color, and pattern, making for a most compelling and enlightening visual experience for visitors of this exhibition. Working with the Museum’s Chief Curator Amy Smith-Stewart, Amari pushes her desire to present a clear presentation of the past, going as far as adding an absurd, drooping, black, electrical wire along the ceiling of the museum to suggest the haphazard way in which the bazaars quickly come together with little concern for regulations. The one element in the exhibition that looks awkward or out of place is the lone neon based plexiglass monolith Nakhoonak-e Aroos/Bride’s Nail (2022). Compared to the rest of the installation in this main room, Nakhoonak-e Aroos/Bride’s Nail is too austere, visually harsh, and abrupt. It could have made sense in a small, darkened room off the main gallery, or left in place and softened a bit by placing it within a fabric setting. The way it is here only serves as an abrupt distraction.

The largest section of the installation hangs on the wall facing the entrance. Titled Bazaar (2020), it combines several opposing patterns of material that is fraying or fancified with tassel fringes at the edges, obsessive stitching, and faded portraits on fabric that suggest a human presence. With this menagerie of wild visual transitions, Amiri projects a strong overall frontal and peripheral depth using a somewhat shortened and weighty perspective. What we are left with is a panorama of eye-catching and unbridled expression that will inevitably prompt a viewer’s smile. Additionally, upon seeing all the visual enticements, it is impossible not to walk up to each vignette and gaze into the dazzling array of colorful and tactile segues. Approaching Bazaar, you next might look up at the collaged fabrics as they reach up toward the lofty ceiling and begin to get the sensation of a lower, child’s eye view—an intended effect? I am particularly impressed with how Amiri handles the far ends in Bazaar. On the left-hand side she uses texture and slightly different shades of light beige, mesh-like fabric and a scallop-cut checker pattern at the top to suggest a sheer dividing curtain that partially blocks another mysterious space. Adding to this narrative, Amiri marks in English and in bold Perso-Arabic script, the different types of businesses one would encounter in such a place. The colorful lettering also adds a festive air throughout the installation, triggering thoughts of adventure and discovery that anyone, especially a child of seven, would experience.

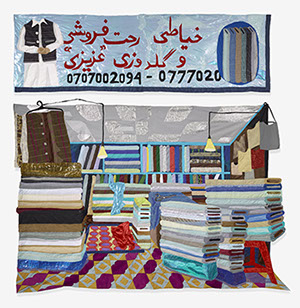

With Azizi, Tailor Shop (2022), Amiri presents a two-part representation of her uncle’s trade, featuring numerous bolts of fabric stacked up on patterned flooring or stood up in shelves, plus two hanging lighting fixtures and a symbolic vest set below a descriptive banner of the trade. The perspective Amiri suggests in this composition creates an active atmosphere. A few details such as the two blue and red fabrics strewn casually about, the haphazard pattern of the ceiling, and the large fabric shears replace the need for people in this narrative. This all comes about with the stack of fabrics on the right that effectively pull you in, directing the eye to the scattered fabrics and scissors. This in turn suggests, without people, a sense of recent activity.

With Azizi, Tailor Shop (2022), Amiri presents a two-part representation of her uncle’s trade, featuring numerous bolts of fabric stacked up on patterned flooring or stood up in shelves, plus two hanging lighting fixtures and a symbolic vest set below a descriptive banner of the trade. The perspective Amiri suggests in this composition creates an active atmosphere. A few details such as the two blue and red fabrics strewn casually about, the haphazard pattern of the ceiling, and the large fabric shears replace the need for people in this narrative. This all comes about with the stack of fabrics on the right that effectively pull you in, directing the eye to the scattered fabrics and scissors. This in turn suggests, without people, a sense of recent activity.

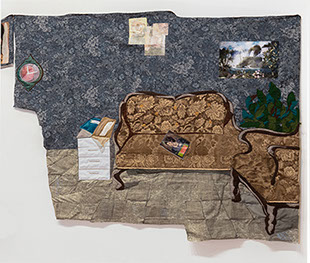

The most clearly descriptive narrative portion of the installation is the Bride’s Beauty Parlor 1 and 2 (2022). The largest section shows two adjoining rooms. On the right hangs a formal waiting area that is far more provincial and proper than the adjacent salon area featured on the left. This business side has many fascinating details such as bottles of hair treatments, hairbrushes, tissue boxes, chrome-trimmed cushioned black chairs, makeover sample photos, mirrors, lighting fixtures and a large expanse of modern white cabinetry. The contrast between these two rooms speaks of the intricate and well thought out duo message in Bride’s Beauty Parlor 1 and 2. A representation of two grappling mindsets, the traditional versus the modern, which come together for one common purpose, hopefully resulting in a most proper and modern bride.

Hangama Amiri, (Left) Brides Beauty Parlor #1 (2022) (detail), muslin, cotton, polyester, velvet, chiffon, silk, leather, suede, inkjet silk print, paper, postcard, iridescent paper, clear vinyl, denim, and found fabric, 63 x 184 inches, Photo: the author. (Right) Brides Beauty Parlor #2 (2022). Various fabrics. Photo: The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, detail of photo by Jason Mandella.

Above and off to the left hangs a two-part banner as part of the Bride’s Beauty Parlor 1 and 2. Here, the fabric collage presents a long rectangular banner indicating some of the products and aspects of beauty one can acquire from a professional makeover. To the right, the banner runs a bit behind a brand-new car, which is adorned with pink flowers and wrapped with crisscrossing gold ribbons topped off with colorful cellophane bows—all suggesting an exterior element. Beauty equals happiness is the message here, all tucked away in every little Afghan girl’s dream, albeit a limiting and often anxiety producing one, as to what it must be like to be a fulfilled, happy, and grownup woman.

When considering the overall message of this installation, one should consider a few elements. The fact that there are no occupants, shop owners or clients in any of these rooms or booths adds a hint of foreboding. You can almost hear the air raid sirens blaring that would have forced immediate flight. Amiri is intent on making sure we realize what is at stake when it comes to basic freedom. For the average American, myself included, it is hard to see Afghanistan other than a place of corruption, civil war, lost rights, little freedom, and horrifyingly harsh punishments. What Amiri has brought to us is another way of seeing Afghanistan; a time between the end of the war with Russia (1979-89) and the beginning of its war with the US (2001-21) when options and rights, especially for women, were beginning to be taken away. Surely, it was not all wine and roses then, but this installation is also very much about the hopes and desires of the children of Kabul before they became old enough to fully understand the reality. It’s about how memories can bring joy, and how children can be amazed by sights, sounds and smells most adults easily overlook. Everything is new when you are young, and Amiri’s two-edged sword of an installation shows us both great love and heartbreaking loss.

The exhibition travels from the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum in Ridgefield, Connecticut, to the Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art in Kansas City, Missouri sometime after June.

D. Dominick Lombardi is a visual artist, art writer, and curator. A 45-year retrospective of his art recently traveled to galleries at Murray State University, Kentucky in 2019; to University of Colorado, Colorado Springs in 2021; and the State University of New York at Cortland in 2022.

Hangama Amiri, Bazaar (2020) (detail), cotton, chiffon, muslin, silk, suede, digitally woven textile, camouflage fabric, sari textile, inkjet prints on paper and canvas, paper, plastic, acrylic paint, marker, polyester, table cloth, faux leather, and found fabric. 168 x 312 inches, Photo: the author.

Hangama Amiri, Nakhoonak-e Aroos/Bride’s Nail (2022). Neon, 41.25 x 37.25 inches. Photo: hangamaamiri.com.

Hangama Amiri, Bazaar (2020) (detail/left side), Photo: the author.

Hangama Amiri, Tailor Shop (2022), muslin, cotton, leather, suede, clear plastic, polyester, silk, velvet, faux leather, wool, iridescent fabric, and found fabric, 113 x 1071⁄2 inches, Courtesy of the artist and T293, Rome Photo: Chris Gardner

Hangama Amiri, Bazaar (2020) (detail/left side), Photo: the author.