“Gordon Parks

The Early Years: 1942-1963”

Rhona Hoffman Gallery, Chicago, June 30–August 4, 2023

by Tom Mullaney

Gordon Parks is considered one of the most accomplished photographers of the 20th century. He was a master of several other talents: filmmaker, composer and the author of three memoirs. Such an acclaimed life is hard to imagine for a child born into poverty in 1912 in Fort Scott, Kansas and who struggled with a succession of irregular, mostly low-paying jobs with little sense of direction until 1942.

Working as a waiter on the Union Pacific Railway, he came across a copy of Vogue magazine. In one of his memoirs, “A Hungry Heart”, he says that he studied its fashion photographs with concentration. He then went out and bought his first camera in a pawnshop for $7.50. “I went to every department store in the Twin Cities seeking to photograph their merchandise without success. But I kept trying.” Vogue, however, would feature prominently in his future.

He met the talented artist, Charles White, at the South Side Community Art Center in Chicago. They became friends and, one day in 1942, he saw White filling out forms to win a Julius Rosenwald Fellowship. When Parks asked what that was, White told him it was a fund “for spooks and crackers with exceptional talent—writers, painters, composers and sculptors”. He urged Parks to apply.

White won his fellowships, and Parks became the first black photographer to win one as well. When asked where he’d like to spend his apprenticeship, Parks replied without hesitation, The Farm Service Administration in Washington, D.C. The FSA was the home of famed photographers Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, Carl Mydans, Jack Delano and was headed by Roy Stryker. Gordon Parks’ life was about to change.

The Rhoda Hoffman Gallery recently mounted a show of his early work that ran from June 30 to August 4. The exhibit consisted of 22 images concentrating on children and African-American life in all its misery and racial, social and economic inequality. Many highlighted the lives of the poor and dispossessed.

On one of his first days, he met a custodian named Ella Watson. Parks asked her to tell him about her life. After hearing her tale of woe, Parks had a memory of seeing Grant Woods’ painting, American Gothic, at The Art Institute of Chicago. Parks took Watson’s photograph (not in this exhibition) with her standing beneath an American flag, holding a mop in one hand and a broom in the other. When Stryker asked him to name the image, Parks answered American Gothic.

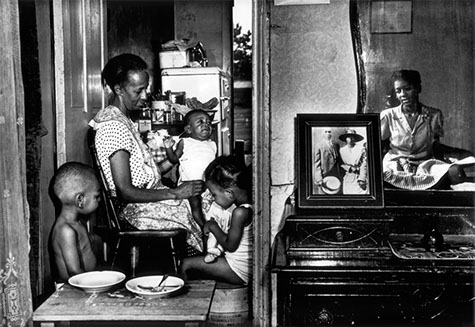

That image encompasses Watson’s life of hard work and a life marred by discrimination. It has become an iconic image in Parks’ portfolio. Stryker told him, “Keep working with her. It will do you some good.” For the next month, Parks photographed Watson’s home, her church and any happenstance occasion. The image, Ella Watson with Her Grandchildren, Washington D.C 1942, depicts the cramped quarters of her tiny apartment. Parks captures Watson’s humanity while showing the malnourished condition of her three grandchildren.

Ella Watson with Her Grandchildren, Washington, D.C., 1942. Gelatin silver print.

Photo: Rhona Hoffman Gallery.

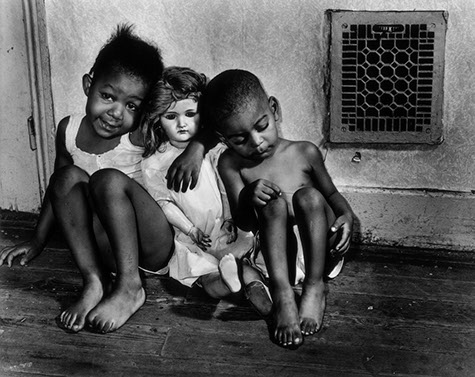

This is one of six images in which children predominate. Others show children at play, at school and dressed up at church. Parks’ instinctive ability to capture children is evident in the emotional depiction Children with Doll, Washington, D.C., 1942. Here are, perhaps, a young brother and sister, sitting on the floor, holding a doll. Her brother is asleep while the girl has an arm around the doll and manages a half smile. They are both scrawny, unaware of their living condition.

Children with Doll, Washington, D.C., 1942. Gelatin silver print. Photo: Rhona Hoffman Gallery.

Parks joined the staff of LIFE magazine in 1948 and, very shortly thereafter, was handling important, assignments, like hanging out with a Harlem street gang and being sent to the 1950 Paris fashion show where his fashion sense shined. He was given twelve pages along with that issue’s cover of LIFE.

Parks, although self-taught, was a master of visual techniques such as choosing angles to shoot, what lighting and settings to choose, atmosphere, and images that contained a strong emotional impact. One of the strongest was Street Scene, Harlem, New York, 1952. It depicts a mournful, completely bushed, black pushcart vendor, sitting on a broken wooden crate with, apparently, no place to go.

Street Scene, Harlem, New York, 1952. Gelatin silver print. Photo: Rhona Hoffman Gallery.

The photos in “The Early Years: 1942-1963” provide foresight into how Parks would develop as a photographer and documentarian of the period. Not all of Parks’ images are depressing. One untitled Chicago shot shows young children in a Chicago school, paying rapt attention to the teacher. Another Chicago 1953 shot, Untitled, depicts a probable church scene, in which Parks cuts the father figure in half to focus on two young girls dressed in their Sunday best facing the camera, one smiling and the other not. A final image, Untitled, Chicago, Illinois, 1953, shows a group of young boys, in the air, arms extended, reaching for a hit ball in a game of stickball. Anyone can relate to the anticipation and joy on the boys’ faces.

Untitled, Chicago, Illinois, 1953. Gelatin Silver Print. Photo: Rhona Hoffman Gallery.

Parks would go on to capture classic images showing the struggle of blacks in their fight for equality. In one, an angry father is gathered around a “Colored” water fountain in Mobile, Alabama in 1956. Others captured images of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King.

Besides his photographs, Parks became the first African American to write and direct a feature film, The Learning Tree, in 1969, based on his best-selling autobiographical novel. His next film, Shaft, was a critical and box-office success.

He continued working the last three decades of his life, ever evolving his style up until his death in 2006. During his life, Parks was awarded the National Medal of Arts in 1988 and was presented with more than fifty honorary degrees. Today, his archives are housed in several institutions, including the Gordon Parks Foundation in Pleasantville, New York, Howard University, the Library of Congress, the National Archives, and the Smithsonian Institution, all in Washington D.C.

Tom Mullaney is the former Managing Editor of the New Art Examiner. His articles have also appeared in The New York Times, Chicago Tribune, and Chicago Magazine.

Washington, D.C. Government charwoman, July 1942 (American Gothic). Gelatin silver print; 9.33 x 7.16 inches. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., LC-USF34-013407-C [P&P]. Farm Security Administration / Office of War Information Photograph.