Gabriel Orozco: "Spacetime"

Marian Goodman Gallery, New York City

by Paul Moreno

One of the most striking pieces in “Spacetime,” is Moon Tree, an example of a series of sculptures Mexican artist Orozco made between 1996 and 2010. An artificial ficus tree sits in a very ordinary pot one could find at any hardware store. The tree is nearly six feet tall, and, within its foliage, a majority of its plastic leaves have been intersected with white paper disks. The artificial tree per se is a bit banal, something that you might find in the corner of an office anyplace in the world. One easily assumes that Orozco found the tree at a home decor or office supply store. His intervention, the insertion of the white disks, does something interesting. First, it makes you look at the ficus, which, in an unadorned state, might not warrant a second glance. The white disks thicken the foliage with their delicate addition of mass and in the way they reflect light and create shadow. Placing an artificial ficus in a room, in most circumstances, would at best be a gesture of bland and easily overlooked elegance. Here it suddenly becomes a considered act. The white disks imply someone cared about this tree. The tree’s second effect is how it plays with the light in the room. The artificial tree, like a cucoloris, casts an organic shadow on the wall. That in itself is quite beautiful, but you might not even see it, because you are looking at the tree. It is as though the tree becomes a tool to make a painting in shadow.

Behind Moon Tree, on the wall, in its shadow, hangs an aluminum sculpture, Modular Sequence: Caterpillar. This five-foot-long rod is formed from a series of alternating large and small shiny aluminum spheres fused together. The larger spheres are then ornamented with more small spheres. This brilliant caterpillar of so many gazing balls almost looks back at the viewer. It adds a depth and shimmer to the Moon Tree shadow. A joke about a caterpillar in a tree makes itself and may or may not have been intentional. What does seem very intentional is that this work when photographed has always appeared to be a horizontal line and in fact appears so on the exhibition website. But here in the gallery, it is vertical. This simple and almost arbitrary decision captures the spirit of the work of Orozco as well as the alegría de vivir of “Spacetime.”

“Spacetime” has been open for nearly a year at the time of this writing. It is expected to be open until the middle of 2023. Its opening was quiet; the press was not alerted; there was no 6 p.m. reception with white wine. I discovered the show quite by accident when I went to see the Lawrence Weiner show upstairs in Marian Goodman Gallery. “Spacetime,” it should be noted, is also under the purview of Marian Goodman Gallery and is described as an an "off-schedule" exhibition. When another gallery vacated their space, Goodman took it over with the intention of using it for a back office. Orozco proposed using the space for the project that is there now. In the same way that Moon Tree plays with notions of natural (the way light falls through trees) and artificial (a tree made of plastic), in the same way that the Modular Sequence: Caterpillar is a horizontal that can also be vertical, “Spacetime” offers something like a small retrospective exhibition but not strictly so.

Gabriel Orozco, Modular Sequence: Caterpillar, 2015. Aluminum, 3 7/8 w x 3 7/8 d x 62 l inches.

Gabriel Orozco, Modular Sequence: Caterpillar, 2015. Aluminum, 3 7/8 w x 3 7/8 d x 62 l inches.

Photo: Marian Goodman Gallery.

If one visits the website for the show, go-spacetime.com, one sees a security camera view of each of the rooms of the exhibition. However, these are actually short amateur videos played on a loop. At this point, as works in the show have been sold or simply swapped out, the video does not even represent the installations as they exist today. The checklist of the show numbers well over a hundred items, and some of these items consist of multiple components.

Throughout his career Orozco has made Working Tables. These works are accumulations of objects that the artist feels live well in each other’s company. It is difficult to say if any one thing belonging to a working table is an art item unto itself. These may include a number of small wax works the artist has playfully shaped; a collection of shells the artist has decorated with grids of graphite, a pyramidal plastic bag of seed pods, yogurt cup caps, models and maquettes for larger works, a pressed flower with a printed puffer, a lemon peel preserved in plasticine, experiments and ideas. Whatever is included is then artfully arranged on a large plinth. One room in the gallery seems to be an immersive and evolving example of this type of work.

.png?crc=473117517)

.png?crc=196853638)

.png?crc=3788290474)

Gabriel Orozco, (Left) Model (White Sea Shells), from Working Table objects, c. 1990s. Graphite on three shells. (Center) Model (Yogurt Caps), from Working Table objects, c. 1990s. (Right) Model (Spitted Lemon), from Working Table objects, c. 1990s. Lemong skin, plasticine. Photos: Marian Goodman Gallery.

Everything I have written about so far is found in just one room of “Spacetime,” ROOM TWO of four rooms that the show occupies.

Along with a number of sculptures and works on paper, the largest room, ROOM ONE, presently contains an example of Orozco’s signature paintings, Samurai Tree (Invariant 28L). All the Samurai Tree paintings are inspired by diagraming the Samurai opening in chess and the sequence of moves that follow it. All the Samurai Tree paintings are identical in composition and always only include the colors red, blue, white and gold—this is the rule. The paintings then differentiate from each other as variables are introduced: size of canvas and distribution of those four colors. Although these paintings are created from a system of rules, the results are paintings that possess a spiraling explosion of vivid color that feel as loose and organic as something that grows in nature; but the paintings also reminds us that nature does not spiral randomly, but in strict patterns. Games, rules, and rules’ exceptions are frequent themes in Orozco’s work. In the Samurai Tree paintings for example, there is a tension in material selection: humble matte tempera paint is the rule, luminous gold leaf is the exception.

Between ROOM ONE and ROOM TWO, a framed work on paper functions as a door. The work on paper, Light Tiger, Lac Du Bourdon Summer, is from 2010 and is part of Orozco’s Corplegados series. Meaning “folded bodies,” these door-size works on paper were made to be folded into a size that could easily fit in carry-on luggage. Made at a time of intense travel, Orozco could take these projects wherever he went and work on them wherever he happened to be staying at the time. They were sometimes worked on unfolded on the floor or the wall; they were sometimes worked on while folded on a desk. They contain elements of collage and cut-outs, and they are inherently double-sided. This example of a Corplegado is somewhere between a portrait of a tree and a splatter painting. Russet branches support green obovate leaves. Two eyeholes cut out of the drawing seem to allude to Moon Tree, which, of course, alludes to Samurai Tree.

If you open the door/drawing, you enter ROOM THREE, which contains a small selection of sculptures and models and a few beautiful, understated charcoal drawings. What most gives one pause is that you suddenly feel you’ve entered a place you should not. The experience does not feel like an exhibition anymore; rather, it feels like you have wandered into the office. On my initial visit, I pardoned myself but was surprised to be invited into the next room, SPACESHIP ROOM. This next chamber of the warren is filled with bright white light. Cubbies line the walls and contain artist objects, some of which are finished work, some of which are models. There are stacks of framed works wrapped in paper. On the day of my first visit, a “Spacetime” attendant was at a folding table unwrapping framed works, archiving them, then rewrapping them. I again pardoned myself for intruding, and she graciously invited me to continue to explore. She also graciously shared information about the project and encouraged me to go up a tiny staircase to THE OFFICES, where a selection of photos and works on paper were either displayed or stored.

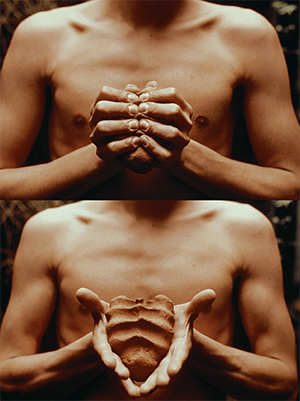

This is where I was happy to see one of Orozco’s best-known images. My Hands Are My Heart (Mis manos son mi corazon) is a photograph in two parts. The top half shows the artist’s chest; his hands are gripping a mound of clay. The lower half shows his hands now open and the clay holding the shape of his grasp. It is a simple and beautiful gesture. The shaped clay in the photograph does in fact become a finished work. A model of this was included in the initial installation of “Spacetime.” This work particularly captures the spirit of the “Spacetime” experiment.

Orozco is letting the viewer behind the curtain but in a way is also saying the curtain was never there. If one sets aside questions like, “Do I know how to apply gold leaf?” when looking at Orozco’s work, one can often see how the thing is made and how one could make a version of it themselves. Gabriel Orozco’s art making is very much about chance, experiment, the rules of games, and breaking the rules of games. In “Spacetime,” he points to the arbitrariness of distinguishing work from model and work from play. This show is honest and vulnerable. He has put his heart out for the casual passerby to explore.

Gabriel Orozco, My Hands Are My Heart (Mis manos son mi corazon), 1991. Silver dye bleach print (cibachrome, 2 parts), 9 1/8 x 12 1/2 inches. Photo: Marian Goodman Gallery.

Paul Moreno is an artist, designer and writer working in Brooklyn, New York. He is a founder and organizer of the New York Queer Zine Fair. His work can be found on Instagram @bathedinafterthought.

Gabriel Orozco, Moon Tree, 1996–2010. Ficus tree, plastic leaves and branches, paper discs, plastic pot, 96 1/2h x 59d inches. Photo: Marian Goodman Gallery.

.png?crc=405390385)

Gabriel Orozco, Samurai Tree (Invariant 28L), 2022. Tempera and gold leaf on linen, 47 1/4 x 47 1/4 inches. Photo: Marian Goodman Gallery.

Gabriel Orozco, Light Tiger, Lac Du Bourdon Summer, 2010. Gouache, pastel on paper, (paper) 72 5/8 x 39 1/8 inches. Photo: Marian Goodman Gallery.