“DEGENERATE! Hitler’s War on Modern Art”

Jewish Museum Milwaukee, February 24–August 30, 2023

by Diane Thodos

Fear and destructiveness are the major emotional sources of fascism, eros belongs mainly to democracy.

–Theodore Adorno1

People were already beginning to forget, what horrible suffering the war had brought them. I did not want to cause fear and panic, but to let people know how dreadful war is and so to stimulate people's powers of resistance.

–Otto Dix

We have to lay our heart bare to the cries of people who have been lied to.

–Max Beckmann2

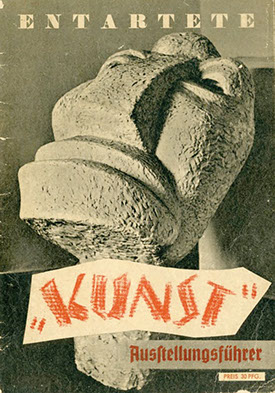

Every now and then displays that reconstruct the history of the infamous Nazi inspired Degenerate Art show of 1937 pop up in major museum exhibitions. These range from the large and scholarly 1991 exhibit at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art to the modestly scaled 2014 show at New York’s Neue Gallery. The Jewish Museum of Milwaukee can be added to this list with their exhibit “Degenerate! Hitler’s War on Modern Art,” a small but comprehensively researched exhibit of Modernist and Expressionist works from the early part of the 20th century. The original Degenerate Art show, “Entartete Kunst,” was the outcome of the Nazi’s project to hunt down and confiscate all forms of Modernist art. German museums were stripped of 16,000 artworks made by members of the Die Brücke (The Bridge), Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity), Blue Rider, Dada, Bauhaus and other modern art movements. From this huge cache, the first Degenerate Art venue in Munich exhibited 650 works to be held up for public ridicule and shame.

The Jewish Museum exhibit has carefully hung displays with explanatory wall texts outlining the historical basis of the newly formed Weimar Republic established after WWI. As Germany’s first experiment in democracy, Weimar was rife with economic and social chaos and political corruption. It was also a period that opened up new public freedoms and creative possibilities in culture and art. This creativity and freedom terrified the Nazis, particularly works depicting the social and economic disintegration following the outcome of WWI and hyperinflation imposed by the Versailles treaty. The latter resulted in a devaluation of the Deutschmark so severe that by November of 1923 one dollar was worth a trillion marks. A barrel of bills could not even buy a loaf of bread, resulting in food riots that broke down law and order. Even after the crisis was stabilized it became one of the motivating factors that helped bring the Nazis to power. The Great Depression of 1929 was the fatal blow to the Weimar era, leaving 30% of the country jobless and leading to a surge in popularity for the Nazi party who came to power in 1933.

What the Nazis feared most—Jews, Bolsheviks, political leftists, cosmopolitanism, sexual liberty, the unconscious—became arbitrary negative labels used in aggressive propaganda campaigns to smear their targets of hatred. One of the exhibit’s wall texts explains the development of this history:

“The National Socialists used culture as a weapon for the 'purification' of Germany. When Hitler became Chancellor in 1933, he decreed that all mediums of art be aligned with Nazi ideology and swiftly instated edicts to remove foreign and so-called "detrimental' influences… The Nazis' strategy to reshape Germany's cultural landscape was monumental in scope and their propagandist campaign against modern art unprecedented. Bans on creation; the purging of state collections; the seizing, sale, and destruction of thousands of modernist works; and mounting exhibitions of shame, including the infamous 1937 Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art) exhibit, played a decisive role in swaying public opinion. Promoting 'untainted, German art reflective of its Nordic values and “superior” Aryan race paved the way for more extreme means of social division and cleansing.”

The Expressionists of the Neue Sachlichkeit or New Objectivity of the 1920’s era made art that protested the ugliness, sickness, and hypocrisy of social reality: truths which the Nazis denied and repressed, not the least for the threat it posed to unveiling the dark sickness that lived within themselves. They saw Modern art’s vast array of creative expression as subversive to their project of totalitarian conformity; individuality had to be censored and destroyed. Modernist art was an evil plot to undermine the German nation and people. Adolph Hitler himself stated “We are going to wage a merciless war of destruction against the last remaining elements of cultural disintegration. All those cliques and chatterers, dilettantes and art forgers are going to be picked up and liquidated.“3

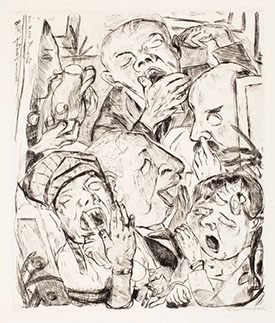

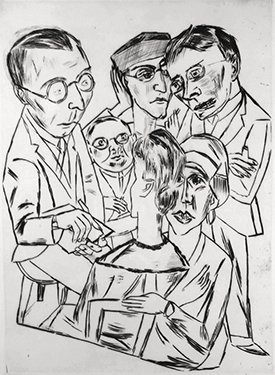

(Left) Max Beckmann, The Yawners, from the portfolio Faces (Gesichter), 1918. Drypoint. Milwaukee Art Museum,

Maurice and Esther Leah Ritz Collection. © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn. (Right)

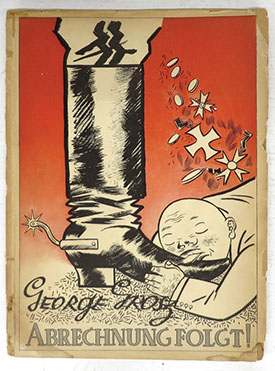

George Grosz, Abrechnung Folgt! (Reckoning to Follow!). Book published by Malik Verlag, Berlin, April 1923.

Collection of Kevin and Meg Kinney.

Most of the Jewish Museum exhibition artworks were small in scale, including many lesser-known artists sourced from local collections. Works were not from the original 1937 Degenerate Art exhibit, but wall texts described each artist’s history while focusing on Nazi persecution and the confiscation/destruction of their works. The texts also detailed those who had works that were included in the Degenerate Art show.

These histories included controversy in the cases of artists like Emil Nolde. Nolde was a dedicated supporter of the Nazi party as early as 1920, attracted to their faux Nordic mythology and intense anti-Semitism. Following the Nazi’s first attempt at overthrowing the government in 1923, Nolde wrote a friend “The Führer is great and noble in his aspirations and a genius man of action.” Despite Nolde’s pandering, the Nazi’s seized over 1,000 of his works from German museums and hung 27 of his works in the Degenerate Art show, more pieces than any other artist.

Emil Nolde, Grossbauern (Rich Farmers), 1918. Etching with aquatint. UWM Art Collection and Mathis Art Gallery, Dept. of Art History at University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee.

Emil Nolde, Grossbauern (Rich Farmers), 1918. Etching with aquatint. UWM Art Collection and Mathis Art Gallery, Dept. of Art History at University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee.

Overall, the scale of cultural oppression was quite breathtaking as artists were systematically suppressed or persecuted in one form or another. This included being discharged from universities and teaching positions, and sometimes being deported to concentration camps. Many chose to flee the country including Wassily Kandinsky, Max Beckmann, George Grosz, Kurt Schwitters and Paul Klee. By 1939 much art that could not be sold at auction to fund the German war machine—some 5,000 paintings, watercolors, sculptures, drawings, and prints—were burned. Much of the art that survived this first assault was destroyed by Allied bombing.

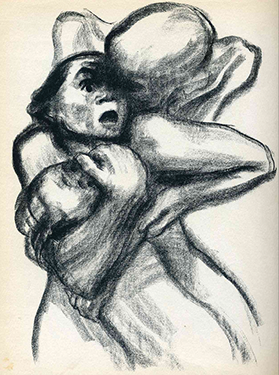

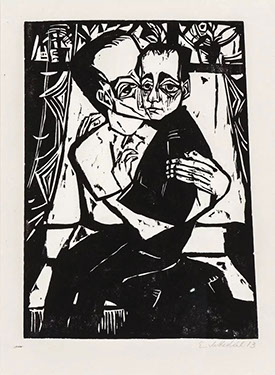

The most memorable works on display in “DEGENERATE! Hitler’s War on Modern Art” were prints by major German Expressionist artists including Ernest Ludwig Kirchner’s Woman Buttoning Her Shoe (1909), Erich Heckel’s Siblings (1913), and Max Beckmann’s The Yawners (1918) and Artist in the Company (1922). Georg Grosz’s Reckoning to Follow! (1923) depicts a grotesque fat bourgeois businessman with pock marked cheeks submissively licking the boot of a military officer while being showered with money and war medals. Equally caustic is his lithograph I have done my part… the plunder is your affair! from his print portfolio series The Robbers (1922). A wealthy bourgeois couple carrying shopping boxes of “plunder” bluntly ignore a destitute one-legged soldier begging on the street, having “done his part” fighting the war so they could handsomely profit. Käthe Kollwitz’s prints bear powerful witness to the moment of eternal separation between mothers and their infants. In Death Seizes a Woman (1934) a mother holding her baby is seized by terror as a skeletal figure comes up from behind her, locking her in its deadly grip. The print’s direct and simple gestural immediacy makes it one of the most emotionally powerful images in her entire oeuvre. There is also the stark woodblock The Sacrifice (1922) from her War print series. The naked form of a harshly rendered maternal figure stands in solemn affliction as she is forced to give her infant up as a sacrifice to war. The pathos of loss is expressed through her strong maternal arms which long to hold on to the fragile life, even as her child is being pulled away from her by the forces of destruction. All these major artists capture the condition of social injustice, tragedy, and disorientation using styles that were powerfully heightened by the graphic innovations they explored in etching, woodcut, and lithographic print media. All expressed the zeitgeist of their time when these artists were at the height of their expressive and artistic powers.

%20from%20war%20rgb.jpg?crc=4012039780)

(Left) Käthe Kollwitz, The Sacrifice from the War Series, 1922. Woodbloc.k Photo: Museum of Modern Art.

(Right) Käthe Kollwitz, Death Seizing a Woman, 1934. Lithograph. Photo: wikiart.org.

(Left) Ernest Ludwig Kirchner, Frau, Schuh zuknöpfend (Woman Buttoning Her Shoe), 1913. Woodblock. Photo: moma.org. (Right) Erich Heckel, Geschwister (Siblings), 1913. Woodblock. Photo: artsy.net.

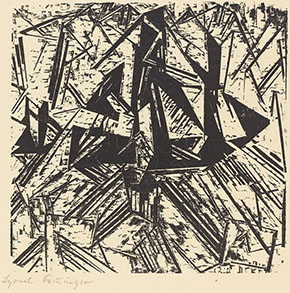

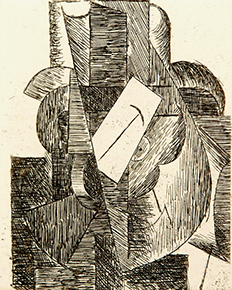

Modernist abstraction was condemned by the Nazis as the product of deranged minds and mental illness, being roundly ridiculed throughout the Nazi’s “Degenerate Art” exhibit. Several examples of abstract work in this current show included small prints by Wassily Kandinsky, Pablo Picasso, and Kurt Schwitters. Abstraction had also seeped into the styles of some of the 1920’s German Expressionists and New Objectivity artists. This can be seen in Lyonel Feininger’s energetic 1918 woodblock Bark and Brig at Sea (1918) and also in the work of Georg Grosz’s common use of Futurist geometry to construct graphic scenes of biting social and political commentary. After Max Beckmann suffered a nervous breakdown as a medical orderly during WWI, his formerly realistic figures became grotesquely distorted, crammed into claustrophobically angular abstract spaces. He stated “I hardly need to abstract things, for each object is unreal enough already, so unreal that I can only make it real by means of painting.”4

Beckmann and many other artists expressed intense anti-war feeling in their work, including Otto Dix, Georg Grosz and Oskar Kokoschka. All had suffered serious trauma witnessing the madness of trench warfare. This accounts for the hallucinatory distortion of figures and space in their work often combined with acutely bitter social observation. Kirschner suffered a serious nervous breakdown while enlisted as a soldier, a condition from which he never totally recovered, eventually committing suicide in 1938.

Socialist sympathizer Kathe Kollwitz lost a son early in WWI. This motivated her to create some of the most powerful anti-war graphics in the history of art. All these artists’ intense anti-war anti-authoritarianism put them on a direct collision course with the Nazis, whose relentless propaganda glorified war, insisting there was no greater honor than martyring oneself as a soldier for the Fatherland. In 1993 Art Critic Robert Hughes commented on the perception of suffering expressed in German Expressionist art coming to resemble images of Holocaust victims. “I looked at the distortion and elongation in certain German Expressionist pictures as though the aesthetic distortions of Expressionism have been made real and concrete…absolute real suffering on the human body by the Nazis.”5

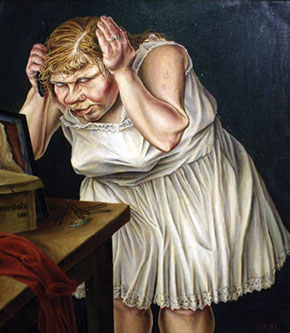

(Left) Georg Kinzer, Frau Vor dem Spiegel (Woman Before a Mirror), 1932. Oil on canvas. Photo: of artnet.com.

(Right) Max Pechstein, Weib vom Manne begehrt (Woman Desired by Man), 1919. Woodblock. Milwaukee Art

Museum, Maurice and Esther Leah Ritz Collection. © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn.

The most memorable painting in the exhibit was Georg Kinzer’s intensely detailed Woman Before A Mirror (1932). A flabby woman combs oily strings of hair before a mirror while her stooped body and sagging breasts are covered in a tent-like camisole. Her face has a bulbous shovel nose, grotesquely rouged cheeks and squinting gimlet eyes that look like they belong to a rabid animal. Her fatuous preening is a common subject of New Objectivity art—monstrous conceit colliding with hypocritical reality. The relentless precision of detail makes it one of the most fascinating and haunting images in the whole exhibition, exposing the yawning gulf between society’s self-perception and its blistering truth.

In similar New Objectivity fashion, Bruno Voigt’s drawings from the 1930’s express the miasma of despair brought on by the Great Depression, reflected in the wasted expressions of crippled drunks in a bar. In another work paranoid men on the street are filled with fear and distrust as they glance over their shoulders with terror, and their eyes darkly foreboding what tomorrow will bring.

Other than Käthe Kollwitz, works by rarely seen women Expressionist artists were on display including Elfriede Lohse-Wächtler’s Lissy (1931) and Martel Schwichtenberg’s Seated Woman with Flowers (1920–21). Schwichtenberg was also a successful designer educated in Dusseldorf and ran her own art studio. She was one of many women who availed themselves of new freedoms under Weimar democracy, breaking out of the imprisoning role of Kinder, Küche, Kirche (children, kitchen, church) by seeking new social roles in education, politics, and work. This resulted in misogynistic attacks by reactionary conservative forces. The media printed sensational stories of Lustmord: gruesome murders of women and prostitutes by violent men. Women’s freedoms were perceived as an attack on traditional masculine German morays, though some of these deaths were also the result of psychotic fits by traumatized war veterans. Lustmord artworks by Otto Dix, Rudolph Schlichter, and Georg Grosz expressed the explosion of uncontrollable madness and violence that could no longer be held in check or repressed by a society in disintegration.

The motivating events that inspired the Milwaukee DEGENERATE! show began with a visit to see the artworks of a major local Milwaukee collector. According to executive director Patti Sherman-Cisler “We were very taken with the artwork and obviously the story about what happened in Nazi Germany; what it did to the culture, what it did to the artists and how it permeated their society. Then we ask our audience if they see those same connections to today.” While the exhibit stays firmly within the lines of presenting a historical analysis of its particular era, the correlation between the meticulously documented social, political and cultural symptoms from the Weimar/Nazi times undeniably struck a chord in me regarding the threat of fascism taking root in the United States and globally. It is well to remember Hitler arrested the transgender community first (a playbook that U.S. red state governors are embracing) followed by the persecution of Jews, homosexuals, gypsies, leftists, the handicapped, and anyone considered “undesirable.”

(Left) Lyonel Fieninger, Bark and Brig at Sea, 1918. Woodcut. Photo: National Gallery of Art.

RIght) Pablo Picasso, L'Homme Au Chapeau (Man in a Hat), 1914. Etching. Photo: mutualart.com.

Theodore Adorno, a Jewish philosopher forced into exile by the Nazis, wrote an important critical study on fascism—The Authoritarian Personality. In it, he defines the tactics of authoritarianism as the politicizing of independent institutions, spreading disinformation, aggrandizing executive power, quashing dissent, targeting vulnerable communities, stoking violence, and corrupting elections. This explains why Dix, Kollwitz, Grosz, and many other artists were committed political leftists for good reason, and why their art was so uncompromising in its defiant stance against the extreme political right wing and conservative forces of the time. Big business and the conservative elite allied themselves with Hitler to destroy the political left and workers movements in a bid for hegemonic control. They overplayed their hand, leading to the eventual fascist overthrow of German democracy. Then as now oligarchic power allied with right wing extremism weakens democracies, corroding their institutions and leading to their eventual downfall. If there is anything I see in this exhibit’s timely historical iteration surrounding German history and the Degenerate Art exhibit it is how Expressionist and New Objectivity art remains as a sharp historical warning about what could happen if we do not succeed in fighting and defeating fascist nationalism in our midst today.

Diane Thodos is an artist and art critic who lives in Evanston, IL. She is a Pollack Krasner Grant Recipient who exhibits internationally. Her work is in the collections of the Milwaukee Art Museum, the National Hellenic Museum, the Smart Museum of Art at the University of Chicago, the Block Museum at Northwestern University, and the Illinois Holocaust Museum among many others. For more information visit dianethodos.com.

Footnotes

1. Theodore Adorno, The Authoritarian Personality (1950), Verso Books 2019 p. 976.

2. Degenerate art - 1933, the Nazis vs. Expressionism https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1QE4Ld1mkoM.

3. Ibid.

4. Max Beckmann, “On My Painting,” 302–3.

5. Degenerate art - 1933, the Nazis vs. Expressionism https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1QE4Ld1mkoM.

Pamphlet for the Entartete Kunst (Decadent Art) exhibit, 1937. Photo: Wikimedia.

Martel Schwichtenberg, Sitzende mit Blumen (Seated Woman with Flowers), 1920–1921. Oil on canvas. Collection of the Haggerty Museum of Art, Marquette University.

%20rgb.png?crc=4277656801)

F. M. Jansen, Der Blinde (The Blind Man), 1925. Oil on canvas. Collection of Kevin and Meg Kinney.

George Grosz, I Have Done My Part, The Plunder is your Affair from The Robbers, 1922. Lithograph. Photo: Art Institute of Chicago.

Max Beckmann, Der Zeicher in Gesellschaft (The Artist in the Company), 1922. Drypoint. Photo: 1stdibs.com