Antonio Obá

Outras águas/Other waters

by Paul Moreno

In the late 1850s, French painter Jean-François Millet completed one of his best-known works, The Angelus (L'Angélus), which depicts two figures in a moment of prayer, in a potato field, in the last light of the day, with a steeple in the distance. The painting was at the center of a controversy that led to the advent in France of the droit de suite—a legal notion that heirs of the creator of a work of art are deserving of compensation if the work of art is resold for significant profit. The painting was also the jumping-off point for a series of important surrealist works by Salvidor Dalí. This painting and its well-known legacy came to mind, not accidentally, when I was viewing a rich and beautiful presentation of painting and sculpture by Brazilian artist Antonio Obá at Mendes Wood DM in New York.

The exhibition contained two sculptures, one of which was called Angelus, (2022). In Obá’s rendition, according to notes he provided the gallery, “five nails are pressed into a beeswax candle which burns down. As the candle melts, the nails fall, striking the bell in their descent to the floor. This work is a votive object, referring to the Angelus tradition that marks the beginning of a rite. Angelus has a ritualistic character to it; the ringing of the bell marks the beginning of a ritual or call to prayer. "…Each nail represents a soul that falls from the fire, a precipitated body that contests our memory, bringing our eyes to the past in reverence.”

This description of the work in terms of its physicality is apt. But if you do not have the rest of his notes, if you cannot peer into the heart that made this work, if, when you look at this sculpture on the wall, you did not think of your eyes being brought to the past in reverence, it does not matter, and therein lies but one beauty of this show. When you see the shiny metal assemblage with its burning candle on the wall, when you see the iron nails hammered into its wax body, when you see the fallen nails, some plunged elegantly into the bowl, and some lost haphazardly on the floor, and if you are there at the magic moment when the candle loses grip of one of the nails and you see it fall with your own eyes and hear the satisfying clang as it strikes the bell, you have all you need. You are pleased with just enjoying this slowly animated work. You maybe find your own narrative. Your own thoughts, memories or fantasies are activated. You revere without trying.

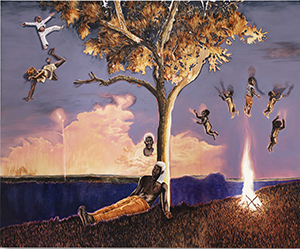

Along with the two sculptures, the exhibition contained 13 paintings, one of which was also called Angelus (2022). This large canvas (90 x 110 inches) is roughly the same proportion as the Millet painting. In the Obá painting, the basket of potatoes from the Millet has grown into a tree, filling the negative space between the two figures in the Millet. The farmer’s pitchfork and the distant steeple in the Millet transmute into a distant ray of light and a plume of fire, respectively, in the Obá. Quotations abound in the Obá painting, but Obá brings something unexpected. He quotes another work of art, Fire on Marlborough Street, a 1975 news photo by Stanley Forman that depicts a woman and her child falling from a collapsed fire escape. Obá takes the falling figures and paints them falling from the tree. The tragedy that the woman and child suffered is changed here: they almost seem to be falling playfully from heaven into a deep purple water. Perhaps it is because they cast a shadow on the sky, as though the sky is just a canvas backdrop on a stage set. Their fall feels intentional and controlled. Obá also adds to this scene a quintette of cherubic children floating around the fire, plus a sort of Pieta; there is a lot here to cling to narratively.

Along with the two sculptures, the exhibition contained 13 paintings, one of which was also called Angelus (2022). This large canvas (90 x 110 inches) is roughly the same proportion as the Millet painting. In the Obá painting, the basket of potatoes from the Millet has grown into a tree, filling the negative space between the two figures in the Millet. The farmer’s pitchfork and the distant steeple in the Millet transmute into a distant ray of light and a plume of fire, respectively, in the Obá. Quotations abound in the Obá painting, but Obá brings something unexpected. He quotes another work of art, Fire on Marlborough Street, a 1975 news photo by Stanley Forman that depicts a woman and her child falling from a collapsed fire escape. Obá takes the falling figures and paints them falling from the tree. The tragedy that the woman and child suffered is changed here: they almost seem to be falling playfully from heaven into a deep purple water. Perhaps it is because they cast a shadow on the sky, as though the sky is just a canvas backdrop on a stage set. Their fall feels intentional and controlled. Obá also adds to this scene a quintette of cherubic children floating around the fire, plus a sort of Pieta; there is a lot here to cling to narratively.

So far, I have only written about two works in the show, connected by one theme. This points to a particular quality of Obá’s exhibition. The things he makes are deeply personal and thoughtfully researched. Content comes from his interest in art history, the history and folklore of Brazil, world religions, the traditions of his ancestors in Africa, and the international influence and consequences of the African diaspora, along with his own personal experience. The layers of these sources undulate and overlap, resulting in oneiric imagery, creating a multitude of entrances for a viewer into the worlds Obá generously creates, with his skillful artist’s hand.

Sankofa, a West African Akan symbol that has spread throughout the African Diaspora, consists of a bird whose head is turned backward while its feet face forward. This suggests that it is only by understanding what has come before us that we are able to move into the future. In his painting Sankofa: cavaleiro (Sankofa: horseman), (2022), Obá transforms the Sankofa into a sort of chimera that is man/horse. The painting depicts a rural landscape with a man astride a horse, but backwards. The man’s eyes are small orbs of light that are green and/or yellow and/or orange. The color feels like it changes as you look at it. These orbs of light are also swarming the scene and suggest fireflies, but in their size and mere presence in this daylight scene they are something otherworldly. The earth in the foreground is painted thick and veiny like a slice of green gold marble, but as it recedes into the background it feels more like Venetian paper. This leads to a ribbon of coral water edged by a blurry ochre olive landscape on the opposite shore. The sky is luminous pale yellow turning a purple gray streaked with gold. Obá’s casual confident strokes paint the white horse with moments of bright blue or rusty shadows, the rider’s pants a rich violet, his shirt a deep wine color, and his features a raw umber. Everything is easily readable but strange and dreamy, hallucinatory, liquid, and even.

Antonio Obá, Sankofa: cavaleiro (Sankofa: horseman), 2022. Oil on canvas,

31 1/2 x 39 3/8 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Mendes Wood DM.

Photo: Bruno Leão.

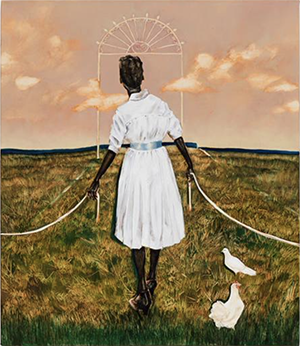

In another painting, Variação sobre Sankofa—Quem toma as rédeas abre caminhos (Variation on Sankofa—Whosoever takes the reins opens the paths), (2021), Obá transforms the Sankofa again, this time into a duet of a hen facing right and a dove facing left. In a way, the hen and dove are both also facing toward the horizon of the landscape. Yet they also are not: Their shadows are not cast into the scene depicted in the painting. Instead, they are cast on the surface of the painting itself. Thus they are, in a way, not part of the scene at all. The central figure of the painting is wearing a white dress and blue belt and shoes with a high heel; we see her from behind. She holds the titular reins, but they are broken; their ends are burning embers or are maybe bloody. She is moving toward a large white iron gate, which is obfuscated by clouds, though the clouds are in the distance beyond the gate. The sky is white or crimson, the landscape is broken, and two pale rays cross the painting, which echoes the swooping lines of the reins. The paint is textured, luminous, complex; deep green and yellow strokes, which represent thick grass that we see as a cross section at the bottom of the painting, evoke the smell of divots in the wet soil formed by the protagonist’s heels.

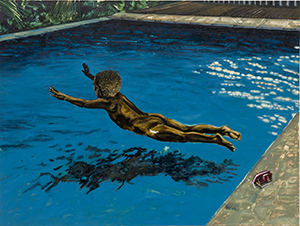

The title of the exhibition, Outras águas/Other waters, is taken from “The Third Bank of the River,” a 1962 story by Brazilian author João Guimarães Rosa. In the story, a man forsakes his community to travel alone up and down a river to learn about himself. Throughout the exhibition, one finds images of solitude, impending journeys, and turnings inward. In the painting Fata Morgana no 1 (2022), a boy is caught in midair as he belly-flops into a pool. The vibrant blue water in one corner glistens white and in the next corner falls into dark shadows. Lush greenery forms a wall on one side of the pool, like a tropical print wallpaper. The stone and wood deck around the pool is casually mathematic. The boy (is it a boy?), arms outstretched and almost lifted, has their gaze not on the water below but toward the greenery, as though they may not descend into the water at all but continue to glide over it and beyond the green. The wavy and undulating reflection of the figure in the water has a life of its own, like a sea creature we can only somewhat understand from our terrestrial view. If the figure does fall into the water, it will collide and become one with the abstraction Obá has placed in the water. The term Fata Morgana describes an optical illusion in which something on the aquatic horizon morphs into something inexplicable, like a boat appearing to be a floating castle. The term also refers to the enchantress of Arthurian legends, who was both virtuous and disruptive, who healed and hindered, who, after centuries of being written about, is not capable of being understood completely. All of these qualities abound in this show, and are, in fact, Obá’s droit de suite.

Paul Moreno is an artist, designer and writer working in Brooklyn, New York. He is a founder and organizer of the New York Queer Zine Fair. His work can be found on Instagram @bathedinafterthought.

Jean-François Millet, El Ángelus, 1857-1859, Oil on linen. 21.8 x 26 inches. Musée de Orsay.

Antonio Obá, Angelus, 2022. Antique bell, bronze sconces, candle, nails, wooden bowl

Courtesy of the artist and Mendes Wood DM.

Antonio Obá, Angelus, 2022. Oil on canvas, 90 1/2 x

110 1/4 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Mendes Wood DM. Photo: Kunning Huang.

Stanley Forman. Fire on Marlborough Street, 1976. Black-and-white photograph. https://rarehistorical photos.com/mother-daughter-falling-fire-escape-1975/.

Antonio Obá, Variation on Sankofa—Whosoever takes the reins opens the paths, 2021, oil on canvas, 27 1/2 x 23 5/8 inches. Photo courtesy Mendes Wood DM.

Antonio Obá, Fata Morgana no 1, 2022. Oil on canvas, 59 x 78 3/4 inches.

Courtesy of the artist and Mendes Wood DM. Photo: Bruno Leão.