True Believers: Benny Andrews & Deborah Roberts

McNay Art Museum, San Antonio

By Christine Zappella

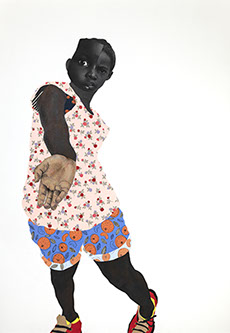

The young black girl that is the subject of True Believers, a collage portrait made in 2020 by Black American artist Deborah Roberts, thrusts her hand forward into our space. She confronts us with not only this assertive gesture, but also the intensity of her gaze, legible through the distortion of photocollage. The girl’s face is two faces, two ages, split down the center. On the left, wide-eyed, a small child regards us with alarm and fear while, on the right, an older girl squints warily and withdraws. The photographic iciness of her composite, monochrome face contrasts with the joyous and bombastic patterns of her colorful clothes. Flat and bright, their floral and fruit patterns recall the landscapes of medieval and early Renaissance paintings and remind us of the innocence of the girl’s youth and its fleetingness. Pictured against a bright white, empty background, the girl seems to exist out of space and time, like a medieval icon or Italian Mannerist portrait. Is she asking for our hand? Help? Charity? Or, given the title, True believer, is the gesture Eucharistic? And how can her obvious vulnerability not remind us of the fragility of the lives of Black youth in America, so often gunned down by the police as well as by neighbors, who are legally entitled to “stand their ground”? These are the kinds of questions about Black identity and the continued Black struggle that are brought up by the exhibition, “True Believers: Benny Andrews & Deborah Roberts,” which closed this February at the McNay Art Museum in San Antonio.

Deborah Roberts (Left), Why aren’t you smiling?, 2018. Mixed media and collage on paper. Collection of Luis De Jesus and Jay Wingate, Los Angeles, CA. © Deborah Roberts. (Center) The feeding ground, 2018. Mixed media and collage on paper. Courtesy of OZ Art, NWA, Bentonville, AR. © Deborah Roberts. (Right) The front lines, 2018. Hand finished pigment print on Hahnemhule Photo Rag Satin 310 gsm paper with glitter silkscreen element. Collection of Marge and Al Miller, San Antonio, TX. © Deborah Roberts.

The exhibition, though, does not only focus on the flat, photographic composite collages of Roberts, who was born in 1962 in Austin, Texas, where she still lives and works. McNay curators René Paul Barilleaux and Lauren Thompson brought the female artist’s works into dialogue with those by Black male artist Benny Andrews, born in Plainview, Georgia in 1930. This comparison is illuminating. Roberts’s enhanced photocollage portraits obviously live in the same crisp, stylized, and sometimes disturbing formal and conceptual wheelhouse as her female contemporaries such as Amy Sherald, Kara Walker, Carrie Mae Weems, Lorna Simpson, Reneke Dykstra as well as women-photographers past like Diane Arbus and surrealist Helen Lovitt. But Roberts had previously expressed admiration for Andrews, whose own painterly-collage style has as much to do with the kinetic materialism of American Abstract Expressionism as it does with the art of self-taught Black folk artists, like his father, George Andrews, who encouraged his son’s artistic development.

Andrews’ obvious admiration for his dad is evident in Portrait of George C. Andrews, made in 1986, which depicts his father, elongated and seen from below. He sits in a throne-like chair in front of a wall, highly decorated and packed with objects that George “The Dot Man” Andrews had painted. As in other of the son’s paintings, collage here is used to reify the existence of the sitter in the room. Fabric is attached to the canvas in the form of real clothing, totem-like objects that Andrews seems able to imbue with the real life-force of the friends and relatives he represented again and again over time. But, having trained at the Art Institute of Chicago and lived the rest of his life in New York City, Andrews’ collages also speak to his reaction to the flatness of the canvas as well as to the material limits of paint that were typical of the art of the mid-to-late twentieth century. His collages’ obvious relationship to these important artistic conversations is evident in the portraits of his artist-friends such as Black American Abstract Expressionist painter Norman Lewis, as well as painter Alice Neel, and Andrew’s wife, sculptor Nene Humphrey, all of which were featured in the McNay exhibition.

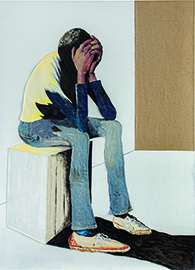

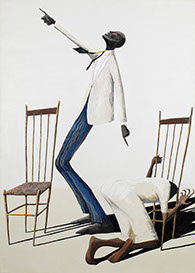

Benny Andrews (Left), Portrait of Despair, 1985. Oil and graphite on canvas with painted fabric collage. (Center) The Way to the Promised Land (Revival Series), 1994. Oil on canvas with painted fabric collage. (RIght) Thanks, 1977. Oil and graphite on canvas with painted fabric collage. All works © 2022 Estate of Benny Andrews / VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY; Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery, New York, NY.

An activist himself involved with the reform of the prison system in New York City, Andrews’s work, like that of Roberts, actively explores the Black body’s relationship with systematic racialized oppression. Nowhere is this more evident than in Andrews’s The Cop, also in the McNay’s permanent collection. Of ambiguous race, the addition of fabric collage to the canvas allows the man to literally stick his nose into the museum’s space, reminding us of the ubiquity of policing of Black people in America and the continued investment of the state in the oppression of people of color.

Accompanied by a well-illustrated catalogue written for a general audience, “True Believers: Benny Andrews & Deborah Roberts” at the McNay was a show with broad appeal. And while Deborah Roberts may be calling attention on a national level to the Austin-arts scene, the McNay, Texas’s oldest contemporary art museum, is itself giving us reasons to look south towards San Antonio. With its critical take on Blackness, beauty, and the body, as well as its celebration of these two under-recognized American artists, Benny Andrews and Deborah Roberts, the McNay Art Museum is making us all true believers.

Christine Zappella is adjunct assistant professor of Neurosurgery at University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, where she researches how the human brain perceives art. She received her doctorate and a master’s degree in Art History from the University of Chicago and also holds a master’s degree in the subject from CUNY Hunter College as well as one in Teaching from Pace University. Christine has held curatorial fellowships at museums such as the National Gallery, DC, the Art Institute of Chicago, and the Frick Collection in New York.

Deborah Roberts, True believer, 2020. Collage on canvas. Collection of the McNay Art Museum. © Deborah Roberts.

Benny Andrews, Portrait of George C. Andrews, 1986. Oil on canvas with painted fabric and mixed media collage. © 2022 Estate of Benny Andrews/VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY; Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery, New York, NY.

Benny Andrews, The Cop, 1968. Oil on canvas with fabric collage. Collection of the McNay Art Museum. © Estate of Benny Andrews/Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.